Note: this post is a duplication from my substack, Stray Bulletin.

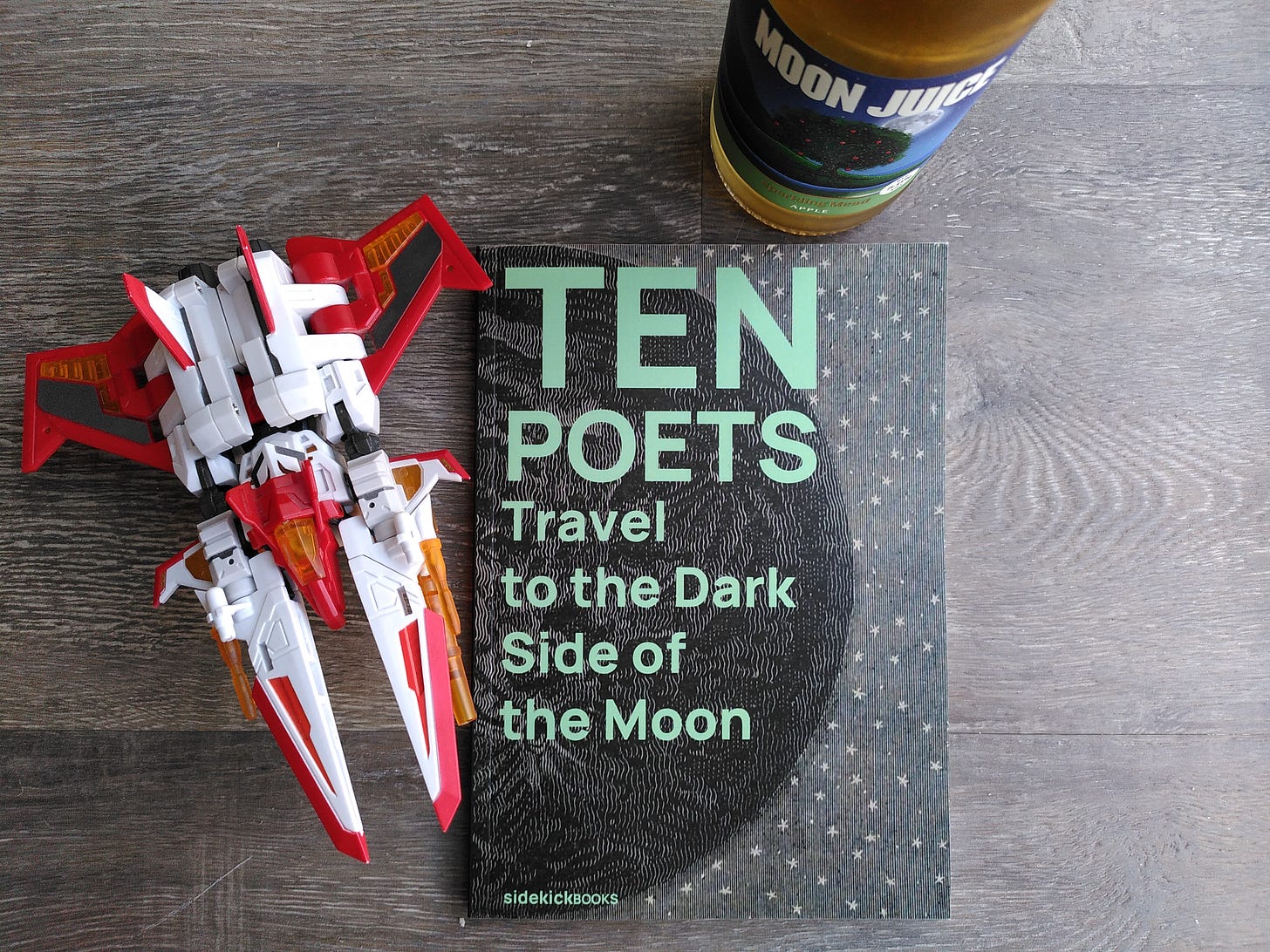

In between running numerous live events over the last couple of months (which I’ll post about soon) I’ve been designing/typesetting/putting the finishing touches to the fifth in Sidekick’s 10 Poets series, Ten Poets Travel to the Dark Side of the Moon. As well as featuring ten brand new, specially commissioned poems, it includes an appendix, in the form of an alternative timeline of Moon landings utilising characters from European comics, and images from James Nasmyth’s The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite.

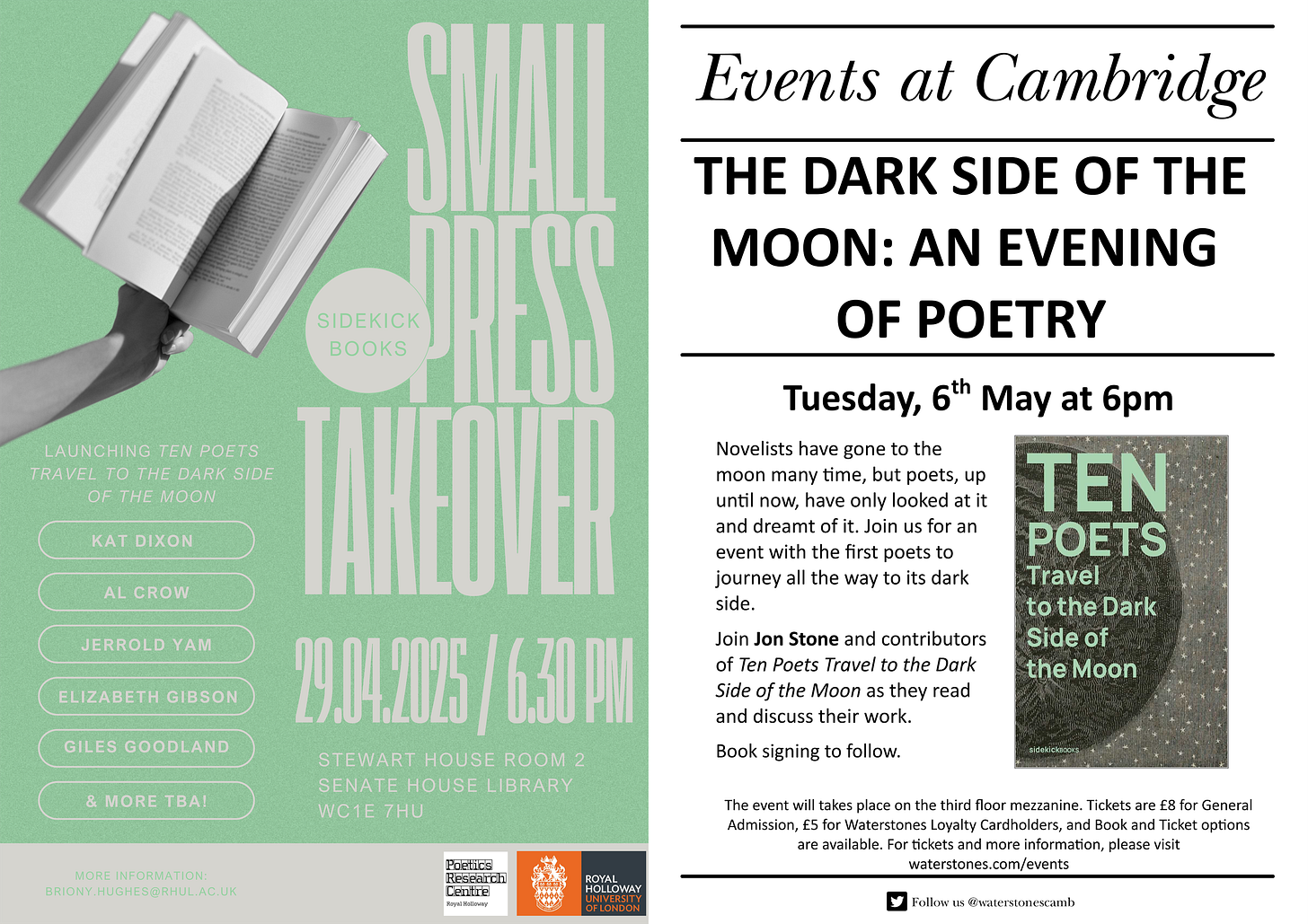

Last week we launched the book in London at one of Royal Holloway’s Small Press Takeover readings at Senate House, hosted by the wonderful Briony Hughes. This week (tomorrow, that is), we’re doing a Cambridge launch at Waterstones, so as an extra little promotional push, here’s a list article, wherein I will introduce you to three more books of space poems, and deliver my run-down of the Top 5 space-themed Transformers.

Three more books of space poems

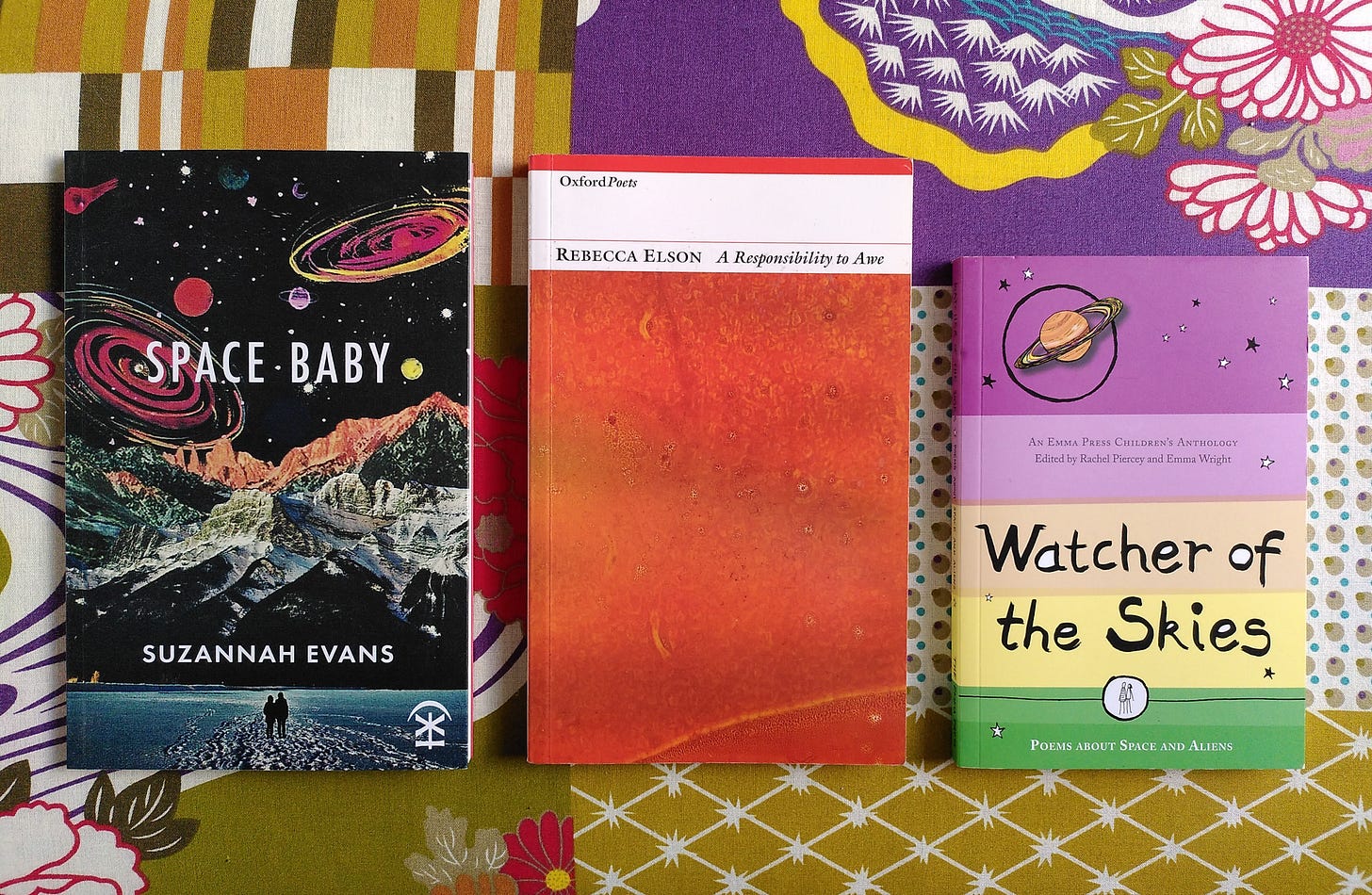

1. Space Baby by Suzannah Evans (Nine Arches, 2022)

Kicking off with an epigraph by Edwin Morgan, one of the first poets to consciously attempt sci-fi poetry, Space Baby is full of poems that fuse astronomical imagery with earthbound scenarios: above a shopper laden with bags, Betelgeuse goes supernova, ‘lurid across the cosmos / like an overripe peach leaking / wet and gold’. Factions of poets — the ‘moon-purists’ and ‘moon-maximalists’ — start seeing moons wherever they go, while in ‘Cassini Love Poem’, the loss of a NASA probe, burning up on entry into Saturn’s atmosphere, becomes a metaphor for self-immolating infatuation.

Evans has a light touch; the poems are zippy and easy to follow, and there are some wonderfully lurid conceits (‘The Glacier Attends its Own Funeral as a Ghost’, ‘Inside Each Universe is Another Universe’, ‘The Dreaming Octopus Colour Chart’) fuelled by a host of intertextual and factual reference points. Here’s the second half of ‘Supermassive Black Hole’:

Above your head the dilating pupil of sky

will show you how everything turns out —

the pinkblue future of undiscovered galaxies

possibilities forking like lighting. The air

is treacly with gravity and you fold yourself

inside it — you chose this —

the rest of time will go on happening.

2. A Responsibility to Awe by Rebecca Elson (edited by Anne Berkeley, Angelo di Cintio and Bernard O’Donoghue) (Carcanet, 2001)

Elson was a scientist first and foremost — she worked at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge in the 1990s, researching globular clusters, chemical evolution and galaxy formation. A Responsibility to Awe was published posthumously, after her early death, and is made up of material gathered by her husband and close friend, including extracts from notebooks.

Science and poetry aren’t entirely incompatible, and some exciting projects have arisen from attempts to bring them together (see Simon Barraclough’s Laboratorio and Project Abeona, run by Andy Jackson, one of the poets featured in … Dark Side of the Moon). But there is something of a tension, since scientific writing aspires toward precision, literalness, practical conclusions, while poetry attempts to leave room, lean into the figurative, pose ever wider questions.

Elson’s grappling with this tension resulted in a singular voice — spare, for the most part, with quick turns, and a focus that rarely drifts from its chosen subject matter, instead pinning it in place. In the punchy ‘What if There Were No Moon’?’, she lists: “No bright nights / Occultations of the stars / No face / No moon songs”. There’s more than space poems here — moths, nuns and salmon are equally keenly observed, while eels and kites are deployed as metaphor — and like Evans, Elson worked hard to connect concepts from her astronomy research to everyday phenomena:

‘Dark Matter’

Above a pond

An unseen filament

Of spider’s floss

Suspends a slowly

Spinning leaf

3. Watcher of the Skies, edited by Rachel Piercy and Emma Wright (The Emma Press, 2016)

A children’s anthology, made eminently more readable both by Emma Wright’s simple, scratchy line illustrations and the plethora of accompanying notes supplied by University of Edinburgh’s Rachel Cochrane. Many of the poems are by adult-audience poets trying their hand at children’s writing, and while this can result in some clumsiness at times, it’s also freed the poets up to be sassier and more direct. Cheryl Moskowitz’s ‘The Algonquin Calendar of Changing Moons’ is mostly a gorgeous list poem (“Wolf Moon / Snow Moon / Worm Moon … Pink Moon / Flower Moon / Strawberry Moon”) while Inua Ellams delivers a lesson in basic astrophysics both teasingly and succinctly: “Everything we are is everything they were. / Everything they were is everything we are.”

I contributed to a short sequence of pastiches called ‘Poets in Space!’ which is also included in this book. Here’s my take on ‘The Thought Fox’:

‘Ted Hughes in Space’

Guest-starring Fox McCloud AKA Star FoxI imagine this midnight moment’s starfield:

Something else is blasting

Through the vacuum’s loneliness

Past the moonbase where my instruments tick.Through my telescope I see no comet:

Something more near

With a flamier tail

Is entering the lunasphere.

Hot, hurtlingly as an asteroid,

A combat spaceship rips through dark;

Fine paws serve a moment, that now

And again now, and now, and nowSlips the ship between debris

And satellites, and neon laser fire

Lights up the sky and the cockpit

Where the pilot boldly plots his courseThrough systems, his eye

A narrowing deepening greenness,

Brilliantly, pluckily

Striking at an evil empireTill, with a sudden sharp shot, Star Fox

Is gone again into a hole in space.

The telescope is empty still. The instruments

Have gone crazy.

Top 5 space-themed Transformers

5. Moonrock

Moonrock is a member of the Astro Squad, a ‘Micromaster Combiner Squad’, meaning his original 1990 toy was only a couple of inches tall in robot mode and transformed into the front half of a lunar missile transport vehicle. He’s made no appearances in any Transformers narrative media, so we only have a couple of back-of-the-box profiles to work off, but he sounds like something of a daydreamer and introspective philosopher, inclined to gaze at the stars all night long in wonder, or endlessly speculate on the nature of the universe.

Here’s a poem about Moonrock by Harry Man, part of my online Mechamorphoses project.

4. Cosmos

Cosmos, who transforms into a bright green Adamski flying saucer, sounds like cyborg Peter Lorre in the original Transformers cartoon. This was a deliberate choice on the part of his voice actor, Michael McConnohie, for reasons never elaborated upon. Because of his novel alt-mode, Cosmos is also a rather squat little robot with gorilla forearms and what appears to be a severe underbite — and since his job is orbital reconnaissance he spends most of his time on his lonesome, making him a rather eccentric character in the round.

Here’s a poem about Cosmos by Claire Trévien — another from the Mechamorphoses project.

3. Astrotrain

As the first major character to transform into a space shuttle, Astrotrain gets heavy rotation in Transformers media as a means of interplanetary transport. Yes — the other Transformers ride around inside him, despite him usually standing the same height as them in robot mode. Unfortunately, his original character profile failed to give him a distinctive personality, which means he’s taken on all sorts of odd roles within the various fictional continuities: a dim-witted petty schemer who tries to take over the world with an army of locomotives; an abused underling who turns against his master; a vengeful widower (?!?); and a non-sentient ‘devil train outa Perdition’.

His second alt-mode, as his name suggests, is a train, which means that if Transformers fiction aimed a few notches higher on the realism scale, he would face the choice of changing into a land vehicle which can only move in a straight line, or a flying vehicle which can’t leave the ground without the help of a solid rocket booster.

Astrotrain once visited the Moon, where he got into a fight with Omega Supreme, the Autobot titan.

2. Countdown

Countdown is another Micromaster, and has only very briefly featured in the stories. His character concept is outrageously good though; he’s a Cybertronian space explorer, landing on alien worlds long before the other Transformers characters and intervening in their politics, Flash Gordon style. As a result, the diminutive size of his 1989 toy and his minimal impact on Transformers lore stands in stark contrast to his standing on thousands of distant planets, where there are presumably statues of him and public holidays held in his honour.

The reason he’s so high up this list, however, is because he’s the only character in the franchise, to my knowledge, who transforms into a moon buggy.

Apparently his toy was a Woolworths exclusive in the UK.

1. Sky Lynx

Sky Lynx is ludicrous. He’s a space shuttle and NASA crawler-transporter that traverse space together and transform into a pair of creatures who share one conscience. The shuttle becomes something like a giant archaeopteryx, the transporter a blue puma with sleek golden head. These two forms can also join back together as a six-limbed monstrosity (a griffin?) that walks and flies, negating the need for the shuttle mode entirely.

Personality-wise, he’s constantly telling everyone how great he is, and providing commentary on his own escapades: “Everybody out! Another perfect flight completed by yours truly, Sky Lynx. Flawless, right down to the landing.”

Here’s a poem about Sky Lynx by my Sidekick co-editor, Kirsten Irving.