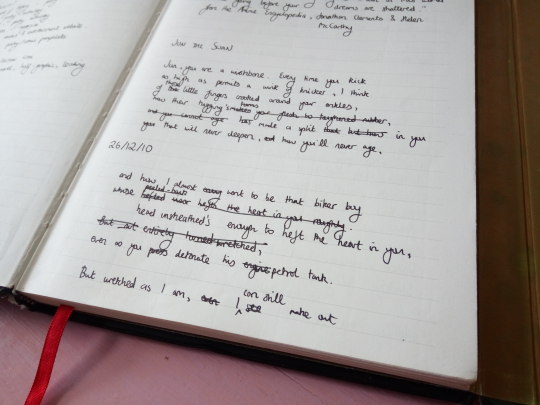

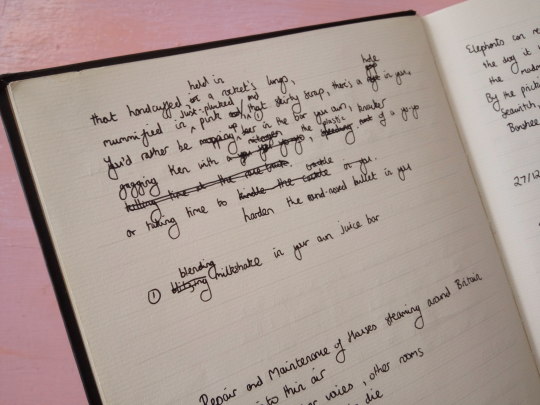

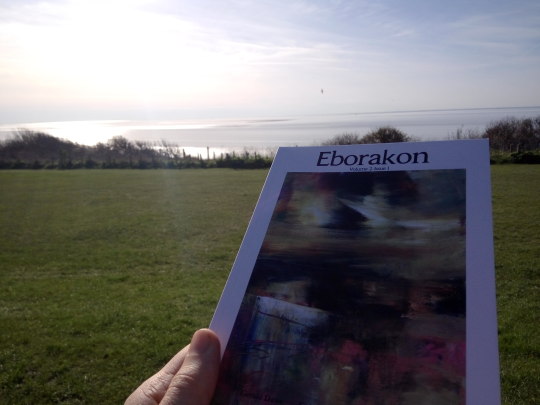

Belatedly drawing attention to the newest issue of Eborakon, published by the University of York, a handsomely produced, neat little poetry journal that also includes visual art and reviews. The editors have included a poem of mine entitled ‘Terminal Ballistics’. It’s one of the poems I salvaged from my years working as a transcript editor in London courts and arbitration centres, and takes its cue in particular from a case concerning naval ordnance. Terminal ballistics (or ‘wound ballistics’) is the study of the behaviour of projectile weapons when they meet their target. I noted down as many pieces of terminology as I could from the experts in the case and substituted them in to lines from various poems of love and tenderness. So it’s a love-hate song of sorts.

The photograph above was taken in Hunstanton on the West Norfolk coast, while waiting for the bus, shortly after having met the dedicated squad of axolotls pictured below.