This post can also be read on my Substack, Stray Bulletin.

DIARY

I keep saying and thinking ‘when I’m settled in’. To living in Cambridge, that is. I use these words to defer certain expectations – this or that will happen ‘when I’m settled’. But I’m not sure what that will look or feel like. The opposite of agitated? Is it me that’s settling, like a leaf on the ground, or is it that my contents are a kind of churned riverbed, a cloud that needs to become a steady layer of sand? Once things stop catching me off guard or causing me trepidation, I will be settled – in which case, I can’t remember the last time I was settled. I’m a worrier – I worry about and at. I’m very suspicious of long silences.

The first couple of weeks of teaching at the new job have been mostly comfortable; that is to say, I’m finding I can talk for a long time and listen attentively, and always have my plan to hand, and I haven’t frozen up at any point to wonder what on earth I’m doing. The hitches and difficulties seem to be the same as those experienced by everyone else, more or less. I haven’t yet got a firm enough grip on my schedule to fit in a lot of writing, however, largely because writing, for me, has always depended on a certain degree of drifting, of unhooking myself from the immediate surroundings. My mind elsewhere. Being away with the faeries. I’m not quite ready to give myself up to that at the moment.

KOSUKE, KISUKE AND SNUFKIN

I’m continuing to make my way, very slowly, through The Village of Eight Graves, in between attending to several other books. The detective in the story, Kosuke Kindaichi, is described here, as in the preceding books, as scruffy, young-ish, always wearing an old serge hakama and sun hat. Several films have been made of his adventures with different actors portraying him, and I was struck, looking at the stills, by how much he resembles Kisuke Urahara, the exiled inventor/shopkeeper from Tite Kubo’s Bleach. Their first names are only one letter apart, and both are characterised as eccentric, oddly dressed and brilliant. Here are there live action outings side by side:

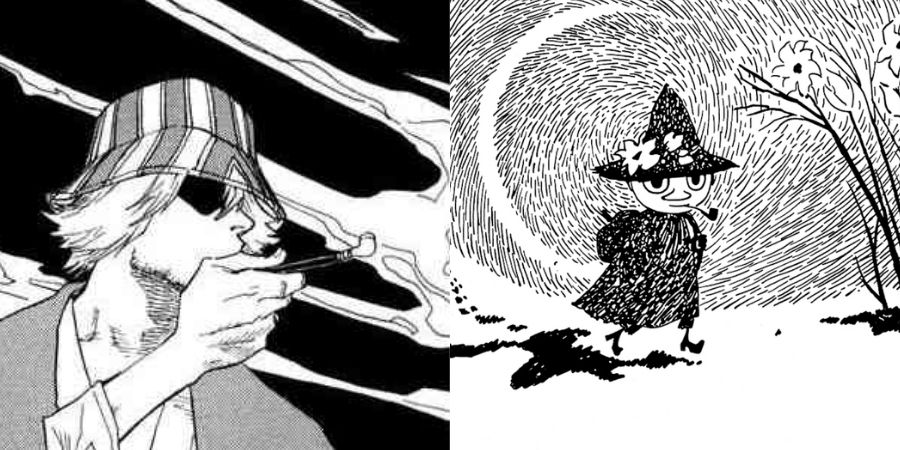

Bleach was first published in 2001, so there’s plenty of scope for the detective to have served as inspiration for the shopkeep, but I can find nothing to substantiate the idea. In fact, Urahara is said to have been inspired by a different character entirely: Snufkin, the vagabond from Tove Jansson’s Moomin books. Here are both in their original illustrated forms:

I would quite like to see all three of them share an adventure someday.

JUST JOSS

(A little late to the party)

I remember encountering, in around 2010, Neill Cameron’s illustrated A-Z of Awesomeness, a lavishly drawn paean to geek culture. ‘A is for Aztecs in Atomic Armour Attacking Anomalous Amphibians’, ‘I is for Indiana Jones Inching Away from an Inebriated Iron Man’, and so on. ‘J’ was for ‘Joss … just Joss’, accompanied by an image of Joss Whedon in the nude, relaxing by a fireside. Ideas for the individual entries were crowdsourced; I would say, therefore, that this is a fair representation of the absurd degree of esteem in which Whedon was held by geek fandom at the time. More so because he was a god of feminism; Buffy the Vampire Slayer and, to a lesser extent, Firefly were supposedly shows that established strong female archetypes, as well as being witty, subversive and self-effacing, a combination that signalled the imminent overthrow of stagnant, male-dominated and heteronormative narrative genres.

Now Whedon is attempting to mitigate the reputational damage caused by revelations about his treatment of actors and crew members, most of them women. Nobody seems to have been particularly surprised by these revelations, coming as they did on the heels of a string of similar busts – men in positions of cultural power found to be abusing that power. But it’s especially unsurprising in this case, since the feminism of Buffy was deeply gestural; that is, it asked to be noticed and acknowledged, a sign that something was expected in return. I often felt uncomfortable watching it in the way I feel uncomfortable seeing men affect an enthusiastically servile manner around women (or a macho one, for that matter – two sides of the same coin).

That does not mean I think Buffy, or Whedon, should have been condemned from the start. But it does seem to me yet another example of a mess resulting from the collective inability to temper enthusiasm, to enjoy things without turning them into sacred objects. I like geek culture, for the most part, but I recoil from it a little as well, because of how it seems to swallow up people’s identities and distort their sense of perspective. Fantasy, sci-fi and adjacent genres have their roots in speculative reconfiguration of the world; they are ways of seeing which relate directly to everyday struggles and politics. Fan worship, at its worst, instead seeks a haven from the everyday, whose borders it then guards until the inevitable collision with reality.

Joss Whedon is, in all likelihood, a caring, creative, rather spoiled guy who doesn’t fully understand why the script has turned on him. If he’d caught heat early on for overstepping boundaries – or if the reception of his work hadn’t done such a good job of convincing him he was a knight in shining armour – he might have made a better fist of telling wrong from right, and not left a trail of destruction. People like him continue to be moulded and made, in part because we continue to believe in a superior kind of person. We believe that greatness is a quality that a person can possess, and behave as if we need that greatness beaming into our lives.