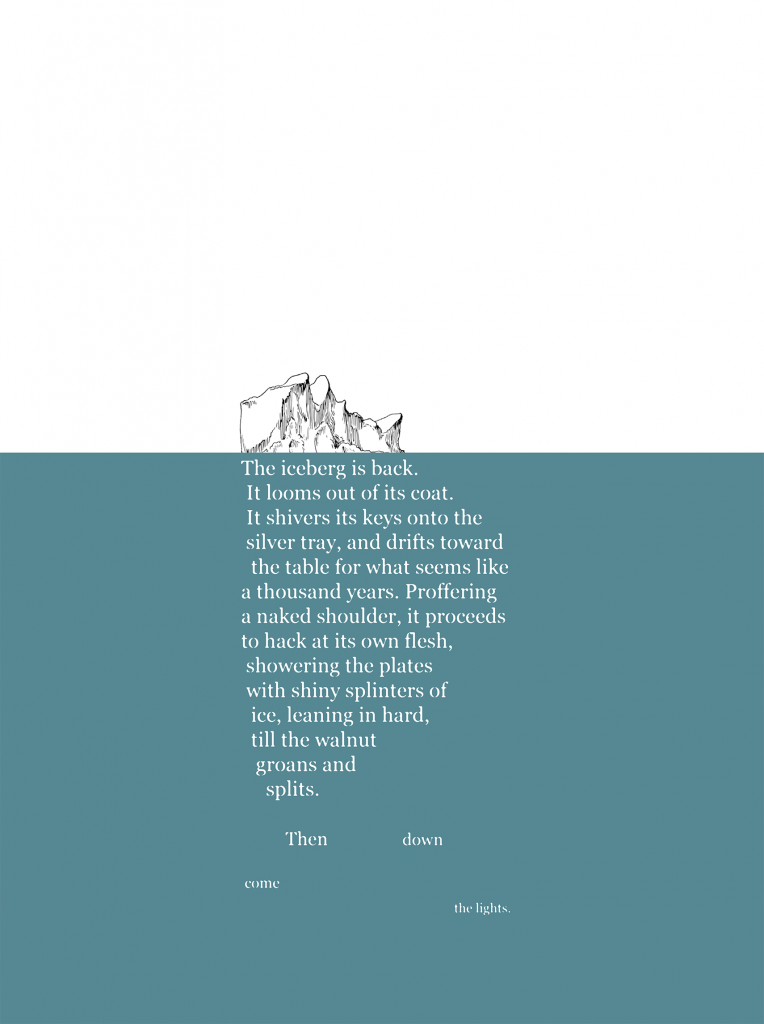

I’ve added a new micro-RPG poem to the website jukebox, based on (and channelling elements of) the Shedworks 2022 game Sable. Here’s an image version:

“A poet of fantastic inversions.” Poetry London

“Multifaceted, mega-fabricated, louche architecture.” Magma

“Voraciously experimental, precociously accomplished.” Poetry International

I’ve added a new micro-RPG poem to the website jukebox, based on (and channelling elements of) the Shedworks 2022 game Sable. Here’s an image version:

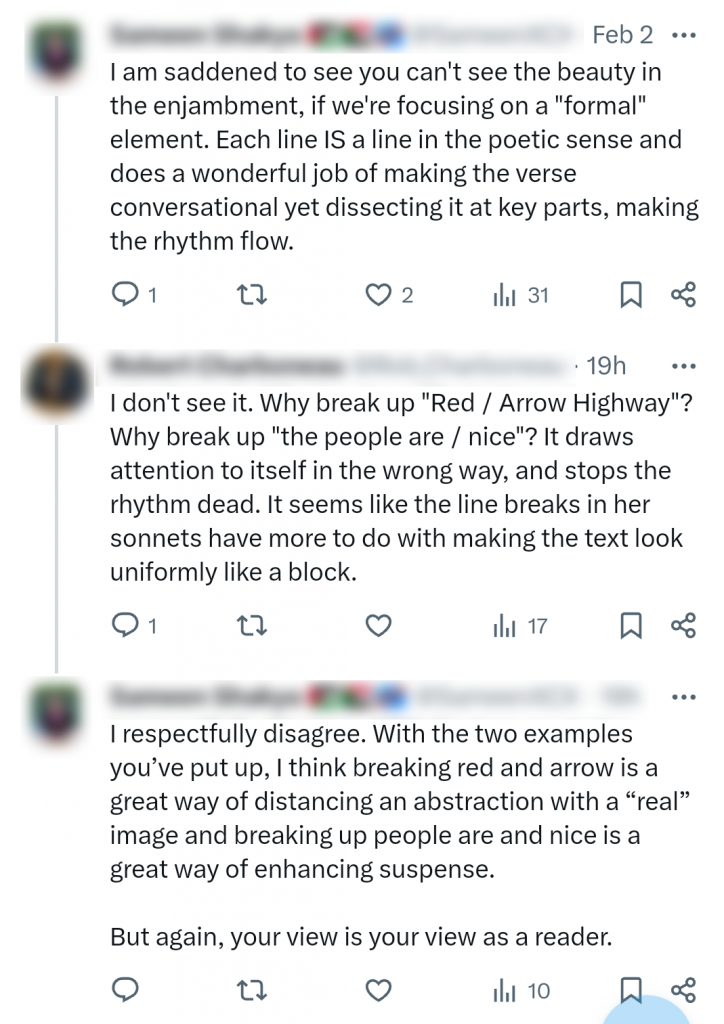

Here’s a rare sight indeed: a discussion of poetic form and its effects (or lack of them) on Twitter/X:

It’s a source of frustration to me that you’re only likely to see such exchanges in the wake of a spat or controversy, as in this case. I don’t agree that social media, as a forum, is especially ill-suited to hosting debates about poetry, or anything else for that matter. The problem is the icy stand-off between attitudes of thought that are equally rigid. On the one hand you have an ever-present, stiff-collared conservatism that pines for orderliness and reassuring authority in everything. From this attitude emanates the demand for a stable ‘definition’ of poetry and a carefully managed system for sorting it into gradations of quality. The worst adherents to this school profess an awe for the ‘beauty’ of classical formalism, but seem to be mainly motivated by their discomfort with both the volume of contemporary poetry and the volatility of the tastes and passions underlying it. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that they regard art primarily as a means for them to pose as refined beings, and resent anything that makes them feel they’re outside a scene. Those on the less extreme end of the scale, meanwhile, are often just bemused that the rules they were told to follow themselves are no longer in play, but lack the means or inclination to work toward a new evaluative framework.

On the other side, we have a supposedly more generous, more egalitarian position that denies, sometimes playfully (but mostly defensively), that there is any kind of consistency at all to what constitutes a poem. Its advocates frequently fall back on flimsy maxims like “I know it when I see it”, or “It’s a poem if it makes me feel something”. The problem here is a failure to recognise just how smugly elitist it can look when the in-crowd insists to frustrated outsiders that their club has no rules. Clearly, there is some sort of mechanism by which a poem leads one or more of us to ‘feel something’, to recognise something of value, and if we’re too lazy or too possessive to make any effort to explain what that is, then we invite speculation that the secret sauce is really favouritism of some kind. There also exists the not-unfair perception that those on the meagre gravy train of arts funding don’t like to talk about why a poem works or doesn’t work because it gets in the way of the endless sensationalist bluster that needs to be performed in order to keep paying the bills and feeding the ego.

Between these positions lies the vast potential to have conversations about the different values and expectations each of us brings to reading a poem, why the same small block of text might provoke feelings of joy in one person, feelings of fury in another, and nothing at all in a third. Occasionally one such conversation breaks out, but it’s all too often a brief interlude in a major bust-up, one that ends once the big factions have retreated to their respective corners and habits, muttering sourly at each other. What if we were to alter our expectations, such that distinct experiences of the same poem were something sought out as an opportunity for learning, rather than something mostly avoided – something which, once brought to light, can only be resolved by the conclusion that one or other person is a nitwit?

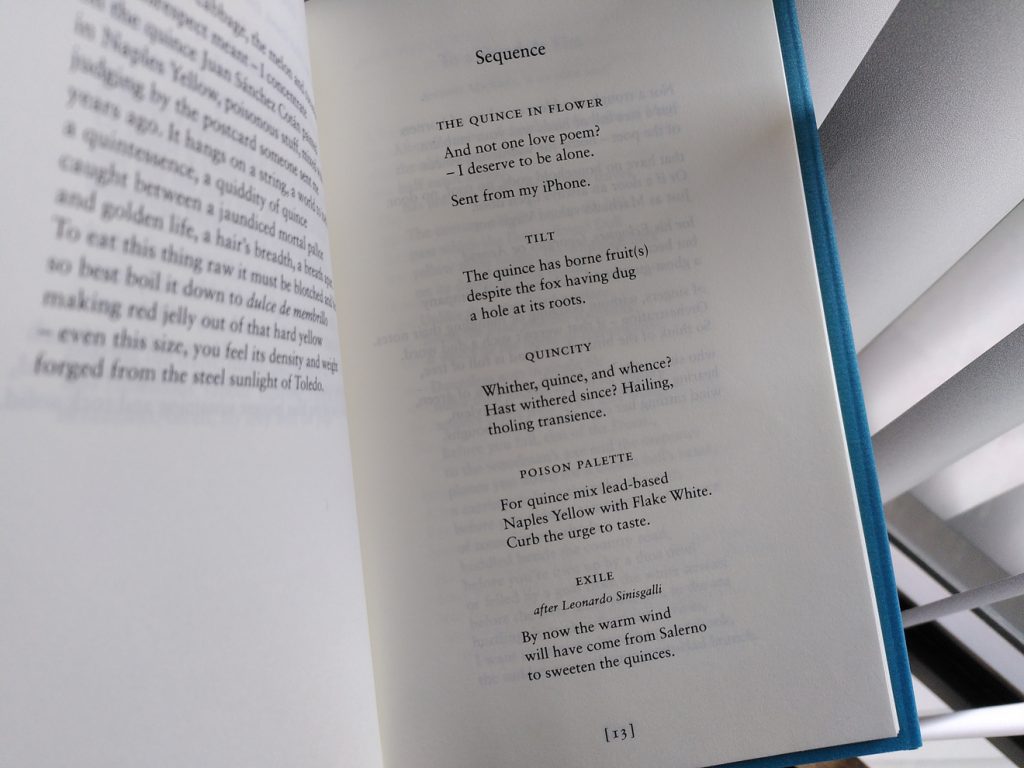

I’m using this poem in an MA class this week – offering it, perhaps unfairly, as the archetypal literary sequence in miniature. I don’t think that’s what it set out to be; the title is punning on ‘quince’ and the whole thing is obviously an extension of that joke (15 lines in total; ‘quince’ is Spanish for 15). But it does serve my purpose. Despite it being made up of individual, haiku-esque tercets, there are strong indications of time passing between each stanza: fruiting follows flowering, ‘Exile’ begins “By now”, and reference is made to ‘transience’. I’m not sure what to make of the weird chronological inversion whereby oil paints turn up long after an iPhone, or the sudden appearance of Shakespearean English – perhaps, in keeping with the theme of renewal, the history of the world is cycling round and round.

The word ‘quince’ repeats throughout like a series of haphazard stitches, and softer echoes of that word are frequent: ‘one’, ‘borne’, ‘whence’, ‘wind’, ‘since’, ‘white’, ‘sweeten’. Hence we have the essence of the sequence, how it differs from a narrative: something is being held in place, squirmingly, even as everything around it changes.

Note: this post is duplicated from my Substack, Stray Bulletin.

The year’s nearly done, so here is the first of two planned posts picking out some highlights from all that I haven’t found time to blog about over the last six months.

Although I’ve made a start on countless digital ‘ludokinetic’ poems, hardly any of them have reached a complete, publishable state. Too much tinkering still required! Also, there’s hardly anyone to publish them with. The New River are one of the few outposts for such projects, and I’m very grateful to editors Amanda Hodes and Florence Gonsalves and their team for taking on ‘I could kiss, say,’, an interactive eco-poem in which you, the reader-player, get to romance the natural/unnatural landscape. Turn your sound on — there’s vocals and a little synth music to go with the movement and play.

I wanted to write so many more reviews and responses to books and individual poems this year! More than that, I want to start proving and exemplifying that reading and critical writing can and should be as expressive and creative as what we deem ‘creative’ writing. You’ll know if you’ve been following my thoughts on this subject that this is because I value poetry and art as an ongoing, inclusive conversation and that my bête noire is the idea of the poet, the writer, the artist as the one who speaks for, at or over the top of others.

But drafts and notes have mostly failed to coagulate into finished, publishable pieces — except in the case of one more ‘Single poem round-up’ where I investigate poems by Sarah-Jane Crowson, Kate Crowcroft and Callie S. Blackstone, published online in Stone Circle Review, Berlin Lit and Rust & Moth respectively. There are links to the pieces in question, so that you can read them in one browser tab and follow my thoughts on them in another.

Short extract from the review itself:

These are all poems about love, of one sort or another — though look what happens to the personal pronouns as each unfolds […] In all three, the traditional pose of the love poem quickly gives way to something more febrile, some more insistent energy which leaves me reaching to pull together the fragments.

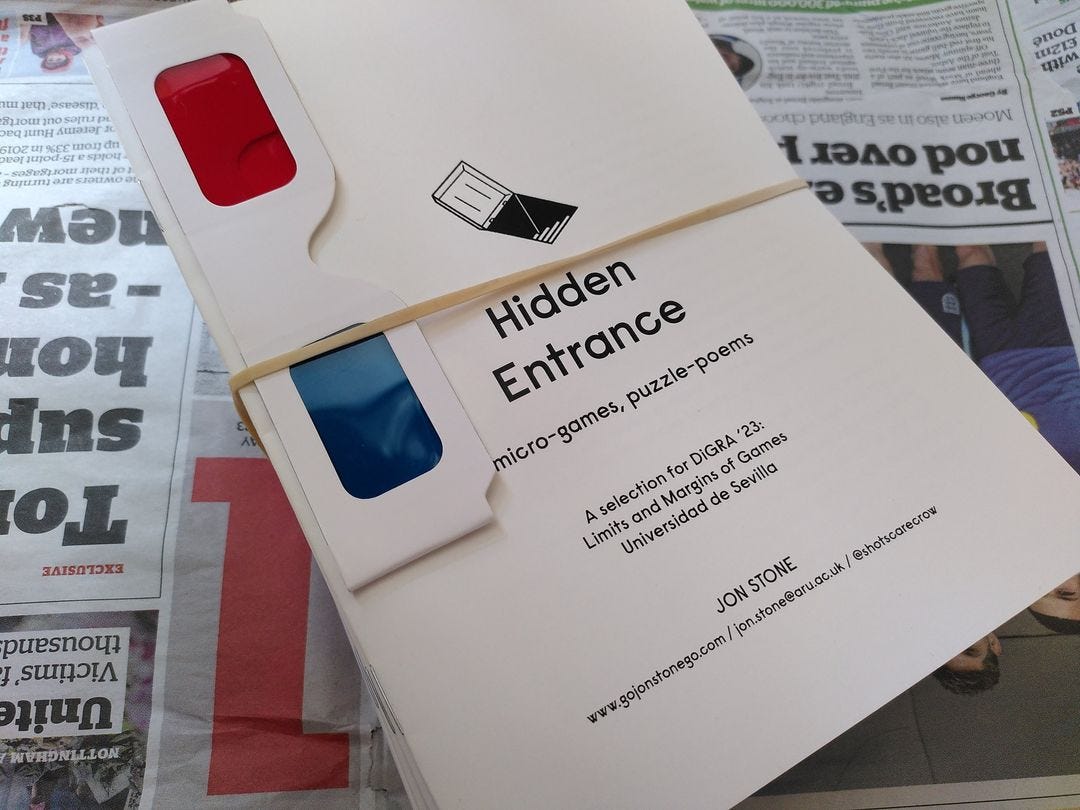

In the long-gone summer I made my way to Seville to present a paper at the DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) international conference. I’ll get to the paper in a later update; for now, I’d like to link you to a digital copy of Hidden Entrance, a tiny pamphlet I put together to hand out to other attendees:

As well as a QR code linking up ‘I could kiss, say,’ and extracts from last year’s Look Again: A Book of Hidden Messages, it includes three brand-new, one-page ‘role-playing’ poems based on recent video games Sable, Citizen Sleeper and Stray.

To my knowledge, no one yet has solved the anagram on the final page. Perhaps I should offer a cash prize?

The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow has been termed a gnostic horror game — not normally the kind of thing that attracts my attention (too many horror games are just slavish adaptations of Lovecraft, or zombiefests). In this case, though, a few things swayed me: it’s a traditional point & click puzzle adventure, utilising primitive-looking graphics to unsettling effect; it’s more indebted to M. R. James than Lovecraft, dealing in the obsessions of a Victorian archaeologist; and it’s set in Bewlay, a fictional village just down the trainline from Bakewell. This does not place it, as some players seem to think, in the Yorkshire Moors, but rather in the Peak District, close to where I spent most of the pandemic.

The script and voice-acting is generally of a high standard, with only the odd dodgy accent, and the story is well-paced, becoming gradually more uncanny the more you uncover of the protagonist’s background and present situation. The backdrops are wonderfully bleak, capturing the feel of the Peaks on a foggy day, and the occasional close-up animation is richly disturbing. Impossible not to think of The Wicker Man as you weigh up the likelihood that the residents of the village are conspiratorially toying with you, keeping the answers just out of reach. The point & click genre lends itself well to this kind of tale, since its puzzles are always so oddly contrived — must I really jump through all these hoops just for some puddings, a horse hair, a pail of goat’s milk? Yes — because in this case, it adds to the sense that you are being led, step by step, toward some grim fate.

As to the ending, I was left a little unsure. It might be that the story lost its footing in the final act, becoming overly predictable, or it might be that I just wanted a little more agency in a supposedly interactive medium. This aside, The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow is one of my favourites of the games I’ve played this year.

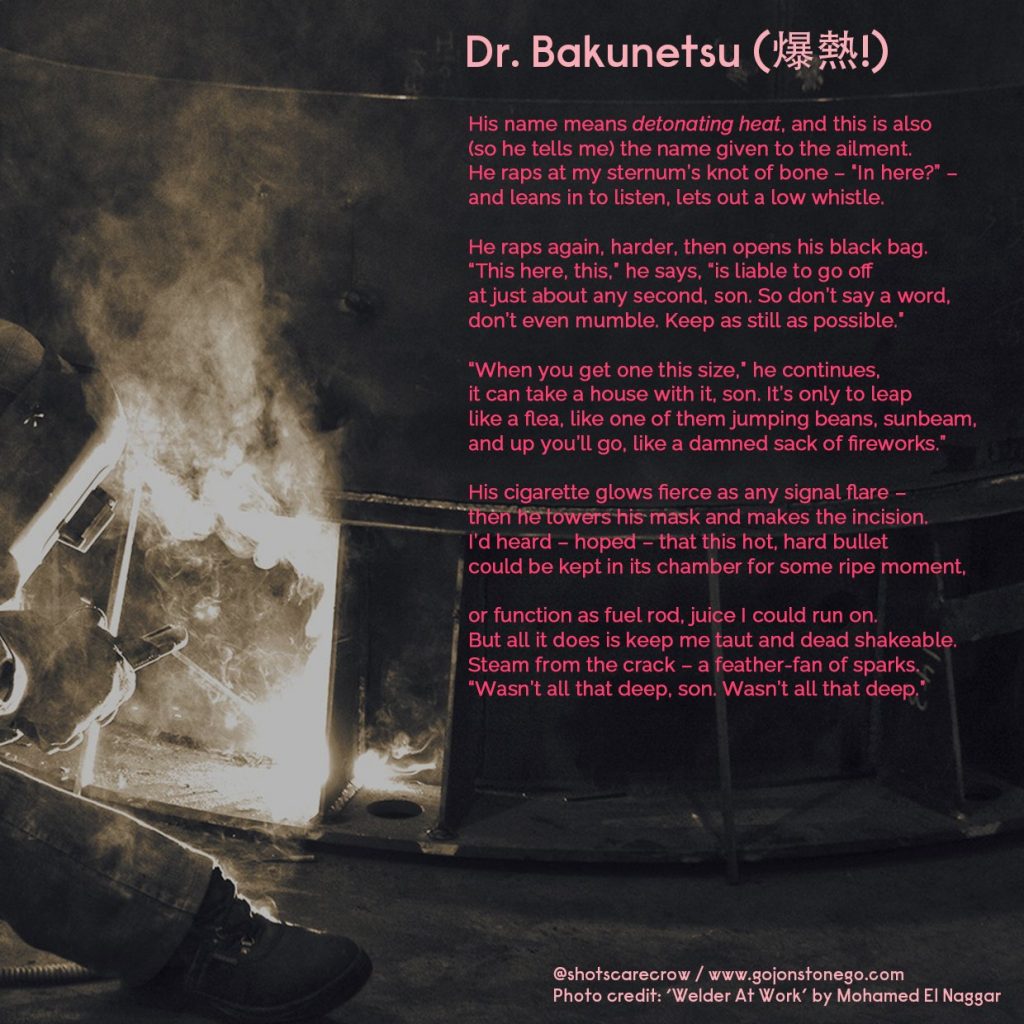

A new addition the the Poems section of the websiteL

Time for another look at three recently published poems, from three different poets in three different journals: ‘Small decrees of dust: A love song with moths’ by Sarah-Jane Crowson, published in Stone Circle Review; ‘The Other Cheek Turn’ by Kate Crowcroft, published in Berlin Lit; and ‘When asked to map the downfall of our relationship’ by Callie S. Blackstone, published in Rust & Moth. I readily admit that having decided to write about the first two I went on an afternoon scavenge for a third ‘Crow’ poet. I thought of Claire Crowther, whose work I admire, but couldn’t find a recent online publication (though the exercise reminded me that her Solar Cruise should be bumped up my to-read list). In the end, having skimmed through a dozen or so different contents pages, I decided I should content myself with a softer associational link — though the reappearance of moths in the title of the journal helps to make it a neat set.

These are all poems about love, of one sort or another — though look what happens to the personal pronouns as each unfolds. Blackstone’s ‘When asked to map the downfall of our relationship’ follows the most straightforward course; it announces its subject matter right away, then gives a bleak, lightly fragmented account of a trip to a lighthouse. But the first ‘you’ only occurs at the end of the first stanza, and there’s just one more after that (“The expensive sandwich shop turned you away”), plus a single ‘us’ and two instances of ‘your anger’. By the end, the addressee has become ‘he’, no longer a subject of the poem but an antagonist.

This is one of the ways the poem undercuts its own mode. That is, it sets itself up as an introspective piece — the speaker poised over a map, hesitant (“my fingers hover”), busy in thought (“images blur together”). It has the hallmarks of a tender address to an ex-lover (“I can sing about you”). The first two stanzas are of equal weight, the lines of decidedly average length. But then the first stanza break cuts off the word ‘you’ from ‘and me’, and it becomes increasingly apparent that something is wrong. The repetitions start to signal distress, emulating the manner of someone trying to make themselves heard (“the place that was my surprise, the place was my surprise // surprise, surprise!”, “I can’t, / I can’t”, “this was supposed to be / this was supposed to be”). The stanza shapes become ever more irregular, sentences run into one another, and as evidence of the male partner’s demanding, abusive and controlling nature stacks up, the lighthouse (“small, suffocating”) starts to look uncomfortably phallic — symbolic of a non-consensual sex act. It seems to me Blackstone first adopts the style and a genre of poem she knows many will find more palatable, using it as a way to smuggle in the tale she wants to tell. This is also reflective, of course, of the way awareness of our own mistreatment creeps up on us. For a moment or two, we think we’re in a love story — then the lighthouse looms into view.

Crowson’s ‘Small decrees of dust’ begins with a prominent ‘us’, and a flower-soaked scene of romance:

The lilacs watched us from the fragrant garden–

heavy and bewildered like a drowning.

OK, the proximity of ‘drowning’ and ‘bewildered’ gives it an uneasy edge, but fragrant gardens and heavy lilacs are strongly suggestive of physical intimacy. And yet the ‘us’ never appears again, nor ‘you and I’ (‘you’ is completely absent). I’d expected the poem to keep the couple locked in its gaze, since this is normally what love songs do, but instead there are a succession of sudden shifts. The second couplet is in italics, implying we’ve moved to a different vantage point — perhaps years have passed. The speaker of this couplet then appears to be interrupted by another speaker in the third, who completes their sentence:

That time before the world was boxed

in a whisper before…before the darted glance, distorted.

Asterisks between the stanzas act as quick cuts, switching up the persona again. There is an ‘I’ and a ‘she’ who never quite settle into distinct figures, though they seem to be united in the closing phrase, “our hair unleashed, / rain-drenched, unpinned, unlocked”. Thematically, the poem quickly cools: there’s only a very short distance between that first fruity couplet and talk of a profound lack of intimacy (“It came to her that she had been alone for so long / that she had become a statue“).

This disjointedness — more complex and jarring than the gradual reveal of ‘When asked to map …’ — is in part a stylistic choice, tying the poem to an accompanying visual collage which mirrors certain images from the poem: the statue, the moth, the twisting of plant and human bodies. But what else is going on? To my mind, this structure evokes the way we look on ourselves from different angles in moments of doubt and hesitance, holding up the mind’s eye like a phone-camera when taking selfies. The person on the phone screen becomes a different entity, someone whose thoughts we can narrate in the third person. It’s also at that moment, posing, that we become statue-like, frozen in the headlamps of our own scrutiny.

The moths in the poem begin as “quiet words”, but the eyes of the lovers also turn into “moth wings”, disinterred from their context (“like a land that is locked, or lost”). So moths here are pieces of memory and language which fade away, but in doing so whirl and flare (they are “ecstatic with decay”). I think this makes ‘Small decrees of dust’ a poem about trying, fitfully, to love yourself, to gather up the evidence that will allow it, including the evidence of having been loved by another.

As intimated in both the syntactic arrangement and imagery of its title, ‘The Other Cheek Turn’ also sets out to mix things up. For some reason, I find myself thinking of it as half way between the other two poems. The first two lines require a double-take (or did from me, at least), since the well-known trope is of a face being struck — a woman striking a man’s after he confesses his betrayal, or a man striking a woman’s to cow her. Here it’s either the face or its expression of “a love so tangible” which is thought of as potentially dealing a blow. This convolution is immediately followed by a much more straightforward, almost cloying declaration:

Your face stalled in a love so tangible

it wouldn’t strike me when I asked it to. Hard

to learn how loved we are

when it’s unfamiliar.

Just like Crowson’s first couplet, there’s an unsettling element — in this case, the allusion to physical violence — but this stanza nevertheless seems to describe a moment of conventional romantic passion. And just like in Crowson’s poem, the sense of a ‘you and I’ vanishes immediately after this point, until the end, when a note is left saying “I want you / to know what is real and what is / not”. (The line break after ‘I want you’ momentarily gives the impression of a love letter, but the rest of the sentence reveals that the writer of the letter seeks control of the narrative). The speaker of the poem goes wandering, conjures a ‘he’ who may or may not be one half of the ‘we’ in the first stanza. It’s more plain here that time is reeling by — there is coffee with a friend, and this out-of-nowhere image:

… the neon

overalls of emergency

workers moved quick

in honeyed light

It reads like an unravelling — the rainbow becoming particles, then neon and honey. Like in Blackstone’s poem, there’s a line of reported dialogue which is blunt, off-register. Here, though, it’s the considered advice of a confidante. Crowcroft’s speaker seems, to my mind, to be trying to find the right groove, to be testing propositions and coming up against further uncertainty. They lie “in sheets — arrhythmic” at the close of the poem, giving in to … what? Perhaps “the charge” is not an accusation but a burden, or even an electric current, so that what the body must accept is a kind of tremendous confusion of the sort that comes from being in love. (Devil’s Elbow, by the way, is a double-hairpin bend in a now disused road in the Scottish Highlands, so the idea here is of someone walking almost back and forth, turning on themselves, in the effort to follow a marked route).

In all three poems, the traditional pose of the love poem quickly gives way to something more febrile, some more insistent energy which leaves me reaching to pull together the fragments. They make me think of how treacherous even simple settings and journeys can turn out to be when the senses are fully activated.

I’ve added a new poem to the site’s poetry jukebox/gashapon machine. This is an old one, first published in 2009, that I’ve re-edited recently, though it’s still a little raggedy.

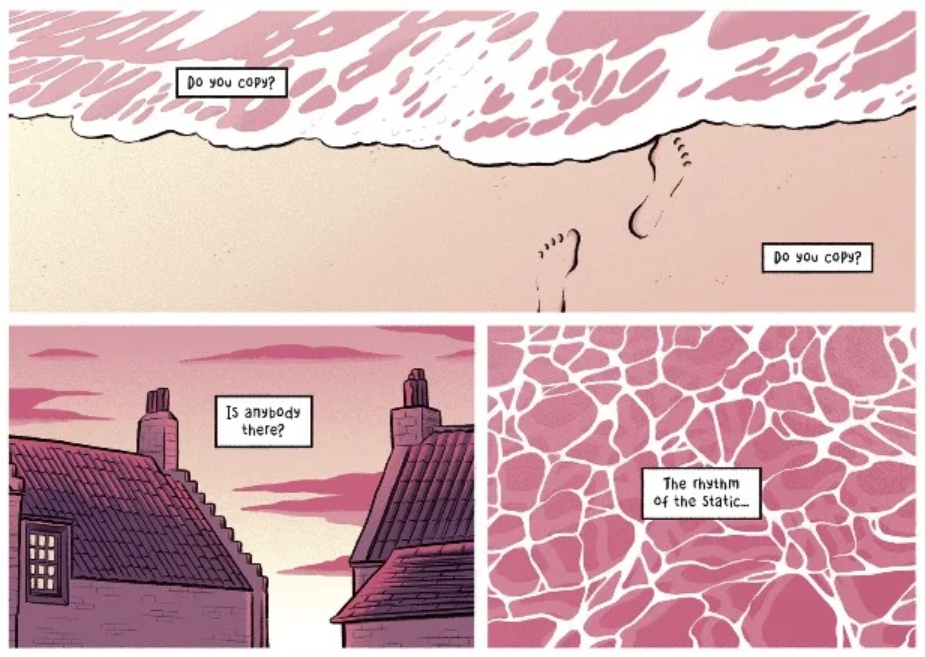

Let’s look at three recently published poems from three different authors and three different online journals. I’ve picked: ‘Heirloom’ by Phillip Crymble, published in issue 13 of Bad Lilies; ‘How to Tank in Overwatch 2‘ by Sara Hovda, published in Cartridge Lit; and ‘Static’ by Chrissy Williams and Tom Humberstone, published in issue 3 of COMP, an interdisciplinary journal.

Is there anything linking these poems? After a short ponder, I thought: something to do with loss, moving forward, having to leave those we love behind. Williams and Humberstone’s ‘Static’, a poem-comic hybrid, gestures to the passing of time constantly, through the images of tidal movement which serve as a backdrop to the words. The speaker has lost touch with seemingly everyone else; they are positioned as a lone radio operator in the opening lines:

Do you copy?

Do you copy?

Is anybody there?

At or around the mention of living in ‘a digital age’, however, the implication is that it is communication technology itself (symbolised by the phone with its redundant/unused compass) which is the cause of this loneliness. The concept of radio and televisual static is married to the texture and sound of the sea through the panel layout, and right at the beginning we see footprints in the sand, leading into the swash.

This post is duplicated from my Substack, Stray Bulletin.

Part one of a mega February-to-May catch-up.

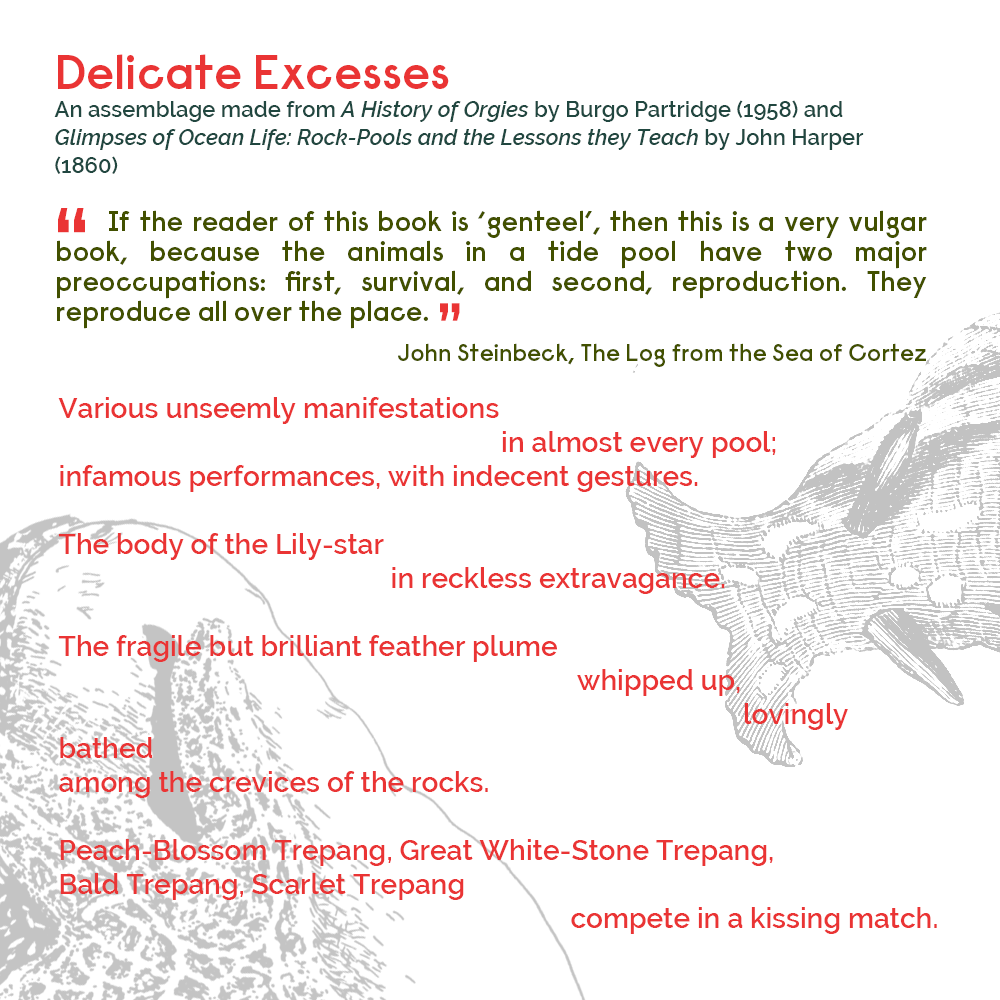

I’ve published a large number of poems over the last decade which have never been collected into one single-author volume. Some are part of Sidekick anthologies and very happily nested there, while others are intended for future books that may or may not materialise. For now, I’m experimenting with making some of them into digital postcards and adding them to the jukebox/gashapon machine on my website. I’m also trying to line up their publication with relevant dates. So ‘Pangolin Documentary’, for example, went online on World Pangolin Day 2023 (18 February) while the below poem (originally published in Aquanauts) was given the postcard treatment in time for John Steinbeck’s birthday:

Change, change — that’s what the terns scream

down at their seaward rocks;

fleet clouds and salt kiss —

everything else is provisional,

us and all our works.

— ‘Fianuis’ by Kathleen Jamie

This paper was originally delivered as a talk at Poetry, Representation and the Archive, a symposium hosted by the University of East Anglia on 25th May 2023. My practice and research mostly concerns the amalgamation of poetry and poetry books with other forms and genres of text, including digital and interactive works, and here I want to discuss digital poetry in particular. I want to talk about the problems inherent in preserving it, and some ideas I have about how its life can be extended.

First of all, I’m going to roughly define ‘digital poetry’ as poetry which is “digital-born” (Ensslin, 2014, p.19); that is, written and designed for publication on or within a digital platform. This does not mean it is totally incapable of being transferred to or translated into a non-digital medium (I will come to talk about this in more detail) but rather that some element of the additional functionality of a digital platform is anticipated in the design. Digital poems are, therefore, poems which physically move and change, often responding to user input. They are poems which are brought into being and animated, at least in part, by computer code which an app or program (such as an internet browser) is used to interpret. There are other, overlapping terms in use – ‘e-poetry’, ‘hypertext poetry’, ‘interactive poetry’, ‘code poetry’ and so on – but ‘digital poetry’ is, at present, the most useful umbrella term for this kind of poetry.

Continue reading “Frayed Ends: On the Longevity of Digital Poetry”