This is an extract from Dual Wield: The Interplay of Poetry and Video Games. When that book was in its draft state, as a doctoral exegesis, I was advised to include a short definition of poetry early on. I found the ‘short’ part close to impossible, so ended up producing the following.

In his Poetics, Aristotle responds to Plato’s condemnation of poets as insidious falsifiers by characterising lyric poetry as an imitative form combining rhythm, language and harmony, the overall purpose of which is to accurately represent human endeavours. Much later, in the early seventeenth century, Thomas Campion set out to demonstrate, in Observations in the Art of English Poesie, that poetry is “the chiefe beginner and maintayner of eloquence, not only helping the eare with the acquaintance of sweet numbers, but also raysing the mind to a more high and lofty conceite” (1602, para 1 of 44). It achieves this due to being made by “Simmetry and proportion,” just as music is, and just as the world is, in Campion’s reckoning.

Later still there are the famous definitions by William Wordsworth (“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity”) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (“the best words in the best order”, as quoted in Henry Nelson Coleridge’s Specimens of the Table Talk of the Late Samuel Taylor Coleridge), both in the nineteenth century. In 1944, in his Introduction to The Wedge, William Carlos Williams wrote:

A poem is a small (or large) machine made of words … As in all machines its movement is intrinsic, undulant, a physical more than a literary character. In a poem this movement is distinguished in each case by the character of the speech from which it arises. (Williams 2009, para 9 of 15)

I choose to highlight these because between them, they account for much of the popular understanding of poetry’s place and purpose, while also appearing to contradict and talk over one another. It is difficult to imagine an alien, faced with this array of descriptions, being able to discern that Aristotle, Campion and Williams are all talking about the same thing.

This functional and conceptual instability is tentatively embraced by many poetry practitioners, as well as those who think deeply about the medium, though there are periodic resurgences in strict adherence to Wordsworth’s creed of spontaneous overflow or Aristotle’s stipulation of verisimilitude. Perloff chronicles two periods in twentieth-century English-language poetry – the period dominated by the modernism of Eliot and Pound, and the counterculture of the 1960s – when the doctrine of natural or common speech came to the fore, such that poets would aim to make the poem a convincing impression of raw communication from the mind or mouth of a thinking and feeling person. Perloff convincingly analyses the results as mere simulations of the natural, increasingly prone to borrowing their effects from televisual media.

As it has become harder to sustain a belief in literary naturality, or in language that speaks to a universal human condition, the public attitude toward poetry has turned toward gentle bewilderment, and poets have increasingly made a pastime out of defending and redefining their art. Pithy or easy explanations tend to be rejected – major poets instead write entire books that recast the poem in new light (Maxwell 2012; Paterson 2018), while newcomers are routinely invited to develop their own personal definition.

Let us suppose that this in itself speaks to something fundamental about poetry’s character, that its reason for being is malleable, equivocal, even provocatively unforthcoming, in a way that paradoxically speaks to its value, as expressed by Nobel Prize winner Wislawa Szymborska:

Poetry –

but what is poetry anyway?

More than one rickety answer

has tumbled since that question first was raised.

But I just keep on not knowing, and I cling to that

like a redemptive handrail. (Szymborska 1996, 14-19)

Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry goes so far as to make the claim that poems are an exercise in disappointment, since they are designed to gesture at an ideal that can never be attained. As Lerner puts it: “The fatal problem with poetry: poems” (2016, 32). Then, more comprehensively:

‘Poetry’ becomes a word for an outside that poems cannot bring about, but can make felt, albeit as an absence, albeit through embarrassment. The periodic denunciations of contemporary poetry should therefore be understood as part of the bitter logic of poetry, not as its repudiation. (73-74)

Lerner goes on to cite John Keats, part echoing Peter George Patmore’s 1820 defence of Keats’ Endymion which describes it as “not a poem at all [but an] ecstatic dream of poetry” (Matthews 1971, 136), but more specifically referring to lines from “Ode to a Grecian Urn” where Keats says “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter”. Those unheard melodies are mere tantalising possibilities, according to Lerner, that readers of poems are endlessly diverted toward, like gold at the end of a rainbow. In the same way, he says, when Emily Dickinson writes “I dwell in Possibility” she means that poetry is the realm of that which is not yet made, not yet real – what the poem can only hint at. If each individual poem raises the mind to a more high and lofty conceit, it is only by talking of an ecstatic dream, never by embodying it.

Lerner’s essay can be regarded as the culmination of a critical trend which has seen the poem repeatedly reconceived in less powerful and commanding terms. In the 1940s, the New Criticism movement promoted the study of the poem as a self-contained object, divorced from any representative or rhetorical purpose. In a pair of influential essays, “The Intentional Fallacy” and “The Affective Fallacy,” William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley argue for the irrelevance of both authorial intent and the emotional response of the reader, calling for the poem to be approached as an object of close study, a bloodless mesh of intricate machinery. The school of reader-response criticism that emerged in the 1960s and 70s foregrounded the role of the reader in mediating and ultimately deciding the meaning of a literary work, in opposition to New Criticism but continuing its work of de-centring the author. Now we have Lerner’s account of the poet almost helplessly gesticulating through the poem, unable even to provide the reader or critic with a gratifying experience, completing the story of a rapid descent from social influence and oratory power. Poets today are left talking wistfully of functions that no longer seem to be in evidence, or of what poetry could, should or might be.

In order to try to reconcile these fluctuations with an understanding that restores to the poem some degree of potency, let us consider it in more technical detail. Lewis Turco’s handbook of poetics, The New Book of Forms, usefully separates poetry into four levels, to which Turco assigns equal importance: the typographical, meaning the visual arrangement of a poem, its layout, symmetry and shape; the sonic, meaning its sounds and sound-patterns, including rhythm and rhyme; the sensory, meaning its descriptive properties; and the ideational, meaning its various themes and ideas. Two of these levels (the typographic and the sonic) represent what William Carlos Williams calls the physical character of the poem, and it is the emphasis on these that helps demarcate poetry from prose. That is to say, poetry is not merely descriptive, not just a transmission, but a medium that draws attention to its own physical character, that asks to be seen, heard and felt as much as (or more than) understood.

How, then, does it make itself seen, heard and felt? To answer that, let us consider Roman Jakobson’s theory of a poetic function of language. Language’s poetic function, according to Jakobson, is that part of linguistic communication that concerns its own materiality and artificiality, its style and form, the way something is expressed or communicated. It is a feature of all linguistic communication, but its importance in relation to other functions of language varies. As Jakobson puts it:

Any attempt to reduce the sphere of poetic function to poetry or to confine poetry to poetic function would be a delusive oversimplification. Poetic function is not the sole function of verbal art but only its dominant, determining function, whereas in all other verbal activities it acts as a subsidiary, accessory constituent. (1960, 356)

So in poetry, the poetic function is brought to the fore; in other kinds of language it has a smaller supporting role. How, then, is it brought to the fore? In explaining this, Jakobson turns his attention to parallelism, or equivalence – the proximity of two or more linguistic units of a similar character, such that we are able to perceive a connection between them beyond the sequential logic of grammar or narrative:

In poetry not only the phonological sequence but in the same way any sequence of semantic units strives to build an equation. Similarity superimposed on contiguity imparts to poetry its throughgoing symbolic, multiplex, polysemantic essence … (370)

What Jakobson is describing is the effect of organising these units so as to make resemblances in their physical character apparent, drawing attention to points of harmony and contrast. Let us look at a typical example of this. In the following stanza of Philip Larkin’s “Aubade,” all but one of the lines are of a near-identical metrical character, and all can be paired according to the end-sound:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify. (Larkin, “Aubade,” 5-10)

Where the penultimate line is shorter, we notice an absence, as if denoting a troubled pause. This is made possible by the pronounced similarity of the rest. Within each line, there is then the similar character of each metrical foot (unrest | ing death | a whole | day nea | rer now), and between pairs of lines, the similar character of the end-sound (now/how, die/-fy, dread/dead). This strategy of organisation allows us to perceive visual and aural structure, and it is this that brings the material presence of the poem into focus so that it is seen and heard, not simply understood. This same strategy can be employed using larger and more complex linguistic constructions. Thus poetry, as Gerard Manley Hopkins says in a citation deployed by Jakobson, “reduces itself to the principle of parallelism” (Jakobson 1960, 368).

But Hopkins goes on to say, in the same quote, that the principle extends to the sensory and ideational levels, to the way in which poetry describes and/or professes thoughts:

[T]he more marked parallelism in structure whether of elaboration or of emphasis begets more marked parallelism in the words and sense … where the effect is sought in likeness of things, and antithesis, contrast, and so on, where it is sought in unlikeness. (368)

Metaphor, then, is also a kind of parallelism, a semantic equation. One thing stands for, or speaks of, an equivalent. It follows that the parallel may reach across and between the levels at which the poem functions, so that the sonic effect of “Flashes afresh,” for example, pairs with the descriptive burden of the word “flashes”. And so long as we encounter poetry in the context of all other texts of which we are aware, the parallel may also be implied to be between a unit within the poem and one without it – as when Byron begins “Sonnet on Chillon” with the line “Eternal Sprit of the chainless Mind,” echoing Pope’s “Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind” from “Eloise to Abelard”.

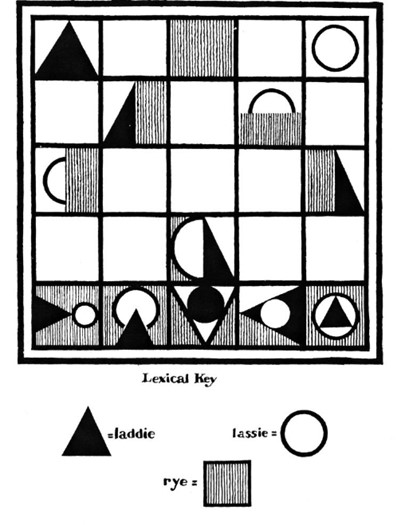

Parallelism is such a broad and flexible principle, in fact, that it permits subgenres of and movements within poetry to touch upon the spaces occupied by visual art, fiction and music. Concrete poetry emphasises the typographic and visual arrangement of the poem to the point where it acts in a descriptive capacity, with the text acting as a visual representation of an object or shape. Max Ernst’s “visible poems,” published in 1934 as part of his Une Semaine de Bonté sequence, are collaged and recontextualised pieces of woodcut illustrations, arranged so that they appear to have the grammatical logic of language. One untitled work by John Furnival, printed in John Sharkey’s Mindplay: An Anthology of British Concrete Poetry, closely resembles a puzzle or gameboard:

Figure 1: “Untitled” by John Furnival (1965), reproduced from Mindplay: An Anthology of British Concrete Poetry.

The principle that allows such pieces to declare themselves poetic works is encapsulated in these lines from “March 1979” by Tomas Tranströmer (2011, n.p., as translated by Robin Fulton): “I come across this line of deer-slots in the snow: a language, / language without words.” In other words, since poetry is based in parallelism, it finds a foundation where there is perceived a parallel between written language and some other visual arrangement. Orally performed sound poetry, similarly, draws on the formal conventions of spoken language while abandoning literary meaning, being more orderly than mere noise while structurally distinct from music, and stretches to its limit the extent to which sound can be used in a descriptive capacity. Wherever there is the trace of language, visually or aurally, poetry may be formed.

The wide ambit of parallelism also makes it difficult to conceive of a truly anti-poetic medium. Successive movements in poetry which have sought to invert or oppose the totality of existing traditions have all fallen into the trap that Lerner wittily describes when he says that avant-garde artworks remain, in spite of their efforts, artworks:

They might redefine the borders of art, but they don’t erase those borders; a bomb that never goes off, the poem remains a poem (…) The Futurists – ghosts of future past – enter the museums they wanted to flood. (2016, 56-57)

Thus, deeply fractured compositions that resist sense-making to the utmost still find their central argument in the display of likeness and unlikeness, even if it is by implicit reference to the conventions they flout.

The next question is: what use does the foregrounding of the poetic function serve? What might be the purpose of a medium based in aesthetic and semantic parallelism? To answer that, I turn to Philip Wheelwright’s elegant elucidation of what he calls “tensive language,” which he positions as the character of all poetic language. Likeness, after all, can only ever be inexact, or it is sameness; therefore in accentuated likenesses there is inherent tension, or conflict. This conflict, according to Wheelwright, may be used to reflect reality far more faithfully than can be achieved with conventional phrasing, since reality is animated by struggle, by ongoing turbulence, is perspectival and coalescent, and a negotiation between the particular and the universal (Wheelwright 1968 , 164-173). In making itself seen, heard, felt and understood, tensive language is language that imitates life itself, that “strives toward adequacy, as opposed to signs and words of practical intent or of mere habit” (46). Wheelwright makes a comparison between the way a poet aims to use words and the way a painter aims to represent nature using only a limited number of colours. What is required in each case is a restless concomitance: combination, indirection, suggestion:

Where language in the more specific sense is in question – language as consisting of words and some kind of intelligible syntax – the problem becomes that of finding suitable word-combinations to represent some aspect or other of the pervasive living tension. This, when conscious, is the basis of poetry. (47-48)

More than mere equivalence, it is tension that results in what Jakobson calls the polysemantic essence of poetry. Each of Turco’s levels multiplies the possibilities for tension between units, and by taking advantage of those possibilities the poet moves beyond the constraints of merely descriptive language.

The result is another well-known characteristic of poetry: ambiguity. Wheelwright prefers the term “open language” so as not to imply looseness or vagueness, saying that poetic language, “by reason of its openness, tends towards semantic plenitude … doubleness of meaning … interplay of meanings and half-meanings … plurisignation” (57). Ambiguity, when deployed skilfully, is not designed to frustrate understanding but to facilitate a more complex or subtle form of understanding, by positioning two or more contrasting implications against one another. In Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” for example, the line “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” simultaneously refers to the power and expanse of Ozymandias’ empire at the time of its peak, and to the near-featureless desert that remains long after its destruction. There is nothing to be gained by discarding one interpretation; the import lies in the ironic contrast between the two. Through such positioning of ambiguous elements, poetry finds ways of representing facets of lived experience and reality that cannot be achieved through logical sequencing alone.

The final question I would like to ask, for the purposes of giving an account of poetry that serves the aims of this chapter, is: what role does the reader play in the poem? From the perspective of New Criticism, they have only to recognise and identify what tensive energies and semantic equations already exist within an individual text. But for critics of the school of reception theory, ambiguity results in potentially boundless depth and restlessness, with scope for continual reinterpretation by different readerships. Umberto Eco identifies this as a defining feature of poetry in his Postscript to the Name of the Rose, where he writes that the “poetic effect” is “the capacity that a text displays for continuing to generate different readings, without ever being completely consumed” (2009, 545). This capacity can only be demonstrated, however, by the process of reading and re-reading. It is the reader’s engagement with the poem that fulfils its potential as a complex and compelling textual system. We might suppose, therefore, that it is the failure to take into account the role of the reader that leads Lerner to regard the poem as hopelessly gesturing toward a state of completion it can never attain. The reader may be cast as operator, as living component in a dynamic web, rather than the recipient who waits at the end of a single-use delivery mechanism.

Brian McHale describes a version of this idea in his explanation of segmentivity, the term proposed by Rachel Blau DuPlessis as the chief organising principle of poetry. McHale contrasts segmentivity to narrativity, the latter of which produces meaning by way of linear accretion, or one thing following another. Where segmentivity is the dominant, the text instead seeks “to articulate and make meaning by selecting, deploying, and combining segments” (McHale 2010, 28) in non-linear configurations. So far, this is another way of explaining what we have already covered, but McHale goes on to say that “segments of one kind or scale may be played off against segments of another kind” (29). Then, taking from another poet-critic, John Shoptaw, the terms “measure”and “countermeasure,” he describes how the sense of the poem is conveyed by counterpointing one layer of segmentation against another, so that there is ambiguity in the very way that the poem is intended to be read or pieced together: line against sentence, phrase against stanza, and so on.

This constructional tension constitutes, says McHale, a series of “provocations” to the reader, whose “meaning-making apparatus must gear up to overcome the resistance, bridge the gap and close the breech” (ibid.). In other words, the reader must experiment with perspectives, methods and approaches in order to squeeze meaning from the poem. They are prevented from simply absorbing it, from passively understanding it, instead having to make decisions about the best way to actively derive sense from what is placed in front of them. This is an imposition liable to frustrate readers who maintain an expectation that the primary purpose of language be descriptive (what Jakobson calls the referential function) or emotive, unambiguously pointed to something outside of itself – but it is only by making this imposition that poetry alerts readers to its broader representational capacity. By wearing its ambiguity outward, such that there is a labyrinthine quality to it, poetry envisages a reader of the kind that matches Aubrey Thomas de Vere’s characterisation of Keats, “one who would rather walk in mystery than in false lights, who waits that he may win, and who prefers the broken fragments of truth to the imposing completeness of a delusion” (de Vere 1849, 345).

There have been many other, more comprehensive investigations of the nature of poetry, but for the purposes of this chapter, the important points in summary are as follows: that it is a medium that draws attention to its own form through parallelism or the paratactic arrangement of linguistic units, not just in terms of meter and lineation but across and between typographical, sonic, sensory and ideational levels; that it does this in order to articulate more than is possible through the sequential logic of grammar; and that by doing so it necessarily positions the reader as an operator, one who must be prepared to actively engage with the ambiguities of the poem’s arrangement in order to uncover its “broken fragments of truth”.