Note: this post is duplicated from my Substack, Stray Bulletin.

A post-January update covering the start of this year and the end of the last one.

Dive, dive!

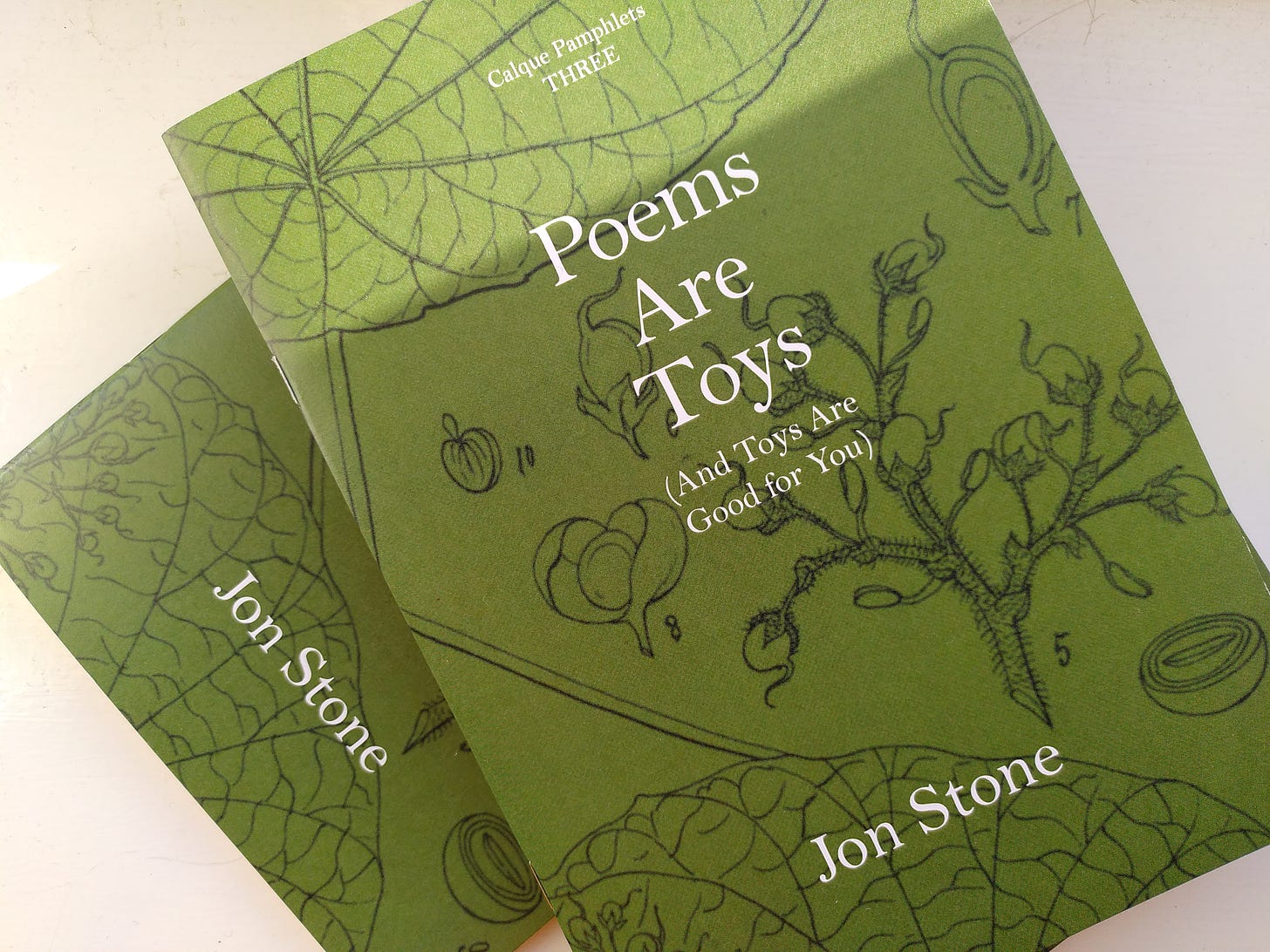

My first publication of the year is a short essay called ‘Next time you dive’ (or How to play a poem), published online in The Friday Poem. It’s a follow-up to my winter pamphlet, Poems Are Toys (And Toys Are Good For You), a considerably longer essay which began as a talk I gave for a conference at York University some years ago. Poems Are Toys argues, in short, that readers and critics ought to treat poems as tools of imaginary play, rather than exhibits to be admired, or coded messages. It’s an anti-elitist screed which took me most of the summer to write.

Here’s how it begins:

Essays making grand statements on English-language poetry are usually pointed in one of two directions: either they’re intended for a general readership, seeking to persuade indifferent readers that poetry is sorely overlooked, or else they’re aimed at poetry’s scattered, somewhat fractious community of readers, practitioners and critics, looking to put some fresh cat among the pigeons. This essay is pointed in both directions at once, with the attendant risk that I fail to meet either audience on terms which they find comfortable. But since my concern is eroding the boundary between general reader and reader of poetry—since I believe, in fact, that this ingrained separation of interests is a symptom of a deeper dysfunction in how we relate to one another—I feel obliged to make the attempt.

‘Next time you dive’, meanwhile, is an attempt at a practical demonstration of what I argue for in theory in Poems Are Toys. I take a poem — ‘Swimmers’ by William Thompson — and discuss it in terms of how I imaginatively engaged with it, batting it around my brain, rather than adopting a pose of critical distance.

Two other reviews in The Friday Poem take a similar approach, one by the journal’s editor, Hilary Menos, and one by my old editor, Helena Nelson. To my mind, both of these pieces are far more readable and instructive than the average critical run-down of a poetry book, because they show us reader-and-book together, in the act of creative negotiation. This is an aspect of writing on/about poetry that has always existed, but it tends to get squeezed out by the impulse to act as salesman for a book we like, or headsman for a book we don’t.

Poor Beleaguered Wizard

For just about my final trick of 2023, I published three ‘Magician’ poems in Berlin Lit, edited by Matthew McDonald. The Magician is the star of his own book, forthcoming … when? I don’t know.

Here’s the first stanza of ‘What’s First Learned of Magic is Later Learned of Love’, a prose poem:

That it cannot be summoned, bid, baited, beckoned, smithed or shook from a tree. That it isn’t made from this or that raw material – and to the extent it’s sealed inside a fortress whose circumference you’ve begun earnestly to map and probe, that fortress is entranceless, its polished walls rising steeply into a sort of smudge of moon and sun.

Basecamp Established, Over and Out

Towards the end of the year I helped organise and host a launch for the Cambridge Writing Centre — a new research group based at Anglia Ruskin University, where I work. I’ve also been hard at work developing a website, logo and podcast for the Centre, as well as planning various events for 2024 with my colleagues. The idea is (a) to have an umbrella brand for the different strands of writing-related research going on at ARU, inside and outside the writing department, and (b) to work more closely with other local literary groups to cross-promote readings, workshops and other activities.

The budget for doing all this is … well, let’s just say we’ll have to take it as it comes, and get a little creative. But hopefully the more we put ourselves on the map, the more opportunities will open up to us.

Maximum Vintage

Before returning from the Christmas break, I managed to finish Rebecca by Daphne DuMaurier. I read the first half the previous Christmas, but it’s my mum’s copy, so I left it a year before resuming. It’s gorgeously written, and the Manderley house and estate makes for a haunting, memorable setting (if only Emerald Fennell had paid as much attention to the titular mansion in Saltburn). It also becomes, gradually, a thriller, a page-turner, and in this respect it presented me with an interesting problem: while reading the final third I found myself wading through the paragraphs of sumptuous description as if they were snow drifts, almost leaping over some of them, since they stood between me and the coming revelations. The book seemed caught between moods, in the same way its protagonist lurches between passion and paranoia. This is almost a kind of ghostly ancestor to ludonarrative dissonance, the term coined by Clint Hocking to describe how a video game can have divergent narrative and ludic priorities, eg. the story demands a pressing-on, a sense of haste, while the game element rewards you for stopping to look under every stone.