This post can also be read on my Substack, Stray Bulletin.

DIARY

I was originally planning to write on two topics: whether or not writers need to read, and disconnections at a near distance. After weighing up which to take on first, I found that the two bled in to one another.

When I teach poetry to students for the first time, I always ask about their prior relationship with it, and there are always a few who say they write it but don’t read it. I understand this; poetry is an expressive tool, and if your major concern is being acknowledged in a world that seems quite happy to roll by with or without you, you naturally lean toward output. The ability to read and enjoy poetry is the result of practice, and we see little apparent evidence of the benefits of putting in that practice. Writers are people of status; readers are just faces in the crowd. The pleasure of reading is private, and its relationship to intellectual or emotional maturity is difficult to trace, for all that we may sense the change within us.

When the topic of writers needing to read was broached on Twitter, two themes came to the fore: firstly, that habitual reading undoubtedly has a positive impact on writing. How could it not? Language is a fearsomely complex system – trying to work if from only one end is going to greatly limit your success. But secondly – and in response to claims that some people’s minds work ‘differently’ – there is the moral case. Why should you expect to be read if you yourself refuse to read? Why should that exchange only run one way? Who deserves to be listened to, who does not listen?

This takes me on to my second mini-topic. I don’t know whether and to what extent this is to do with my getting older, or to the damage wrought by the pandemic, or to do with specific painful events in my life, or to do with capitalism or Toryism or the ubiquity of digital media (probably all of the above), but I am finding it particularly difficult to connect with new people around me at the moment, and feel this particularly acutely when we have, on paper, much in common.

It’s not just a case of my feeling shut out; I also struggle with unwillingness on my part. That is to say, I simultaneously feel an intense desire to connect and an equally intense hesitance. I have to work hard to resist feeling mildly exasperated, or bored, or judgmental. All talk feels like small talk. When this is coupled with my perceiving that the other person is also pushing a boulder up a hill, feels the same ambivalence toward me, it lends itself to a feedback loop, in the same way that friendships tend to spring from rapidly accelerating mutual intrigue.

Now, my memory of last being a stranger in a strange land is hazy, but I’m sure I remember the process of getting to know people involving a lot of generous, unguarded gestures from all parties. When I make one of these now, not only is it often not reciprocated, but I may end up feeling I’ve made the person uncomfortable – as if I were doting. I’ve become accordingly more restrained.

Hard for me to know, though, how it looks from the other side. Hard for me to judge whether someone is genuinely keen to maintain emotional distance, or wants me to offer much more, wants me to put all I’ve got to offer on the table. Or whether they themselves simply don’t know what is misfiring.

Thinking back again to writers who don’t read, I wonder if it’s possible for a collective – a stratum of a society, say – to be damaged to the point where the combined ability to extend care and understanding toward others becomes far outstripped by the need for the same care and understanding. For the need to write (and, hence, to be read, to have one’s experience validated) to completely overtake the capacity to take on board ideas and experiences that are of an alien character.

I wonder sometimes even about people who read voraciously – whether they are really exposing themselves to the risk of disorientation, of intellectual and emotional hurdles, or whether they have found a way to read with blinkers on, sifting the material for what reassures them. I wonder if this is what the judgement that a work is ‘beautiful’ sometimes relates to, and whether there is a connection with standards of beauty in people – the beautiful being that which is devoid of threat, which will not change you.

I may be drawing together too much. I may be overly haunted by some advice given to me in the midst of a series of bad dates last year. Without going into the details, it pertained to What Women Want (or what answers their subconscious psychological needs, say) and lo, it was something I could not see myself ever being able to provide, nor being inclined to fake. Perhaps, then (I say to myself), the people I meet now need things, and are able to ascertain very quickly that I am not a provider of these things. Much as I am offering handouts, worksheets and group discussion to students who may struggle to see past their need for acknowledgement and validation.

And what do I want? What do I mean by this ‘connection’ I say I’m looking for? Perhaps the same thing – perhaps more than anyone can give. To be read, to be listened to, to be made safe.

Or maybe I just want to run into someone who will play couch co-op games with me.

VIDEOGAMES

I’ve recently started playing Dishonored 2, from Arkane Studios – a little nervously, since the original Dishonored was a game I felt didn’t need a sequel. There’s a strange dissonance to both titles whereby the story casts you as a cautious avenger, only killing the most despicable enemies, while the various systems (enemy behaviour, player abilities, level layout) entreat you to become a brutal, supernatural night stalker and murder-machine. This is even more pronounced in Dishonored 2, which begins by making a sore point of the fact that you’ve been framed for the deaths of your political rivals, before handing you a knife, pistol and crossbow and making it trivially easy to terrify and tear apart enemies.

As an example of what is now termed an ‘immersive sim’, it’s designed to facilitate different approaches and playstyles. There are videos of players who approach each level as a dance floor – after practising their moves for countless hours, they will release a video of them performing an expertly choreographed ballet of mayhem and mutilation. An electric-shock mine attached to a severed head is thrown into the air, landing on another enemy just as he whirls round to face the protagonist, surprising yet another into falling into the harbour, and so on.

I prefer to try to ‘ghost’ each level, getting through it without being seen or heard while robbing every purse and rooting through every drawer and cabinet. But what I really enjoy is testing the boundaries of the game’s realism and watching it devolve into the uncanny. I can yank a guard officer up onto the roof of his own lodge, take his money, then slingshot away – the A.I. doesn’t know how to jump or climb down, so after recovering from the mugging, he will simply stand there on the narrow roof, pondering to himself.

In a similar move, I rescue two civilians about to be shot by the local religious fanatics. I stow them in plain sight on a dusty first floor balcony while the cult members below yell, “Come out of hiding!” and light bombs. When one of my rescuees notices I’m carrying the unconscious body of an underworld boss, he cries out in terror and, lacking anywhere to run to, cowers before me. He is still in the same position, on the same balcony, when I return half an hour later, after having made a deal with the cult and stolen every single one of their pistols from right under their noses.

FICTION

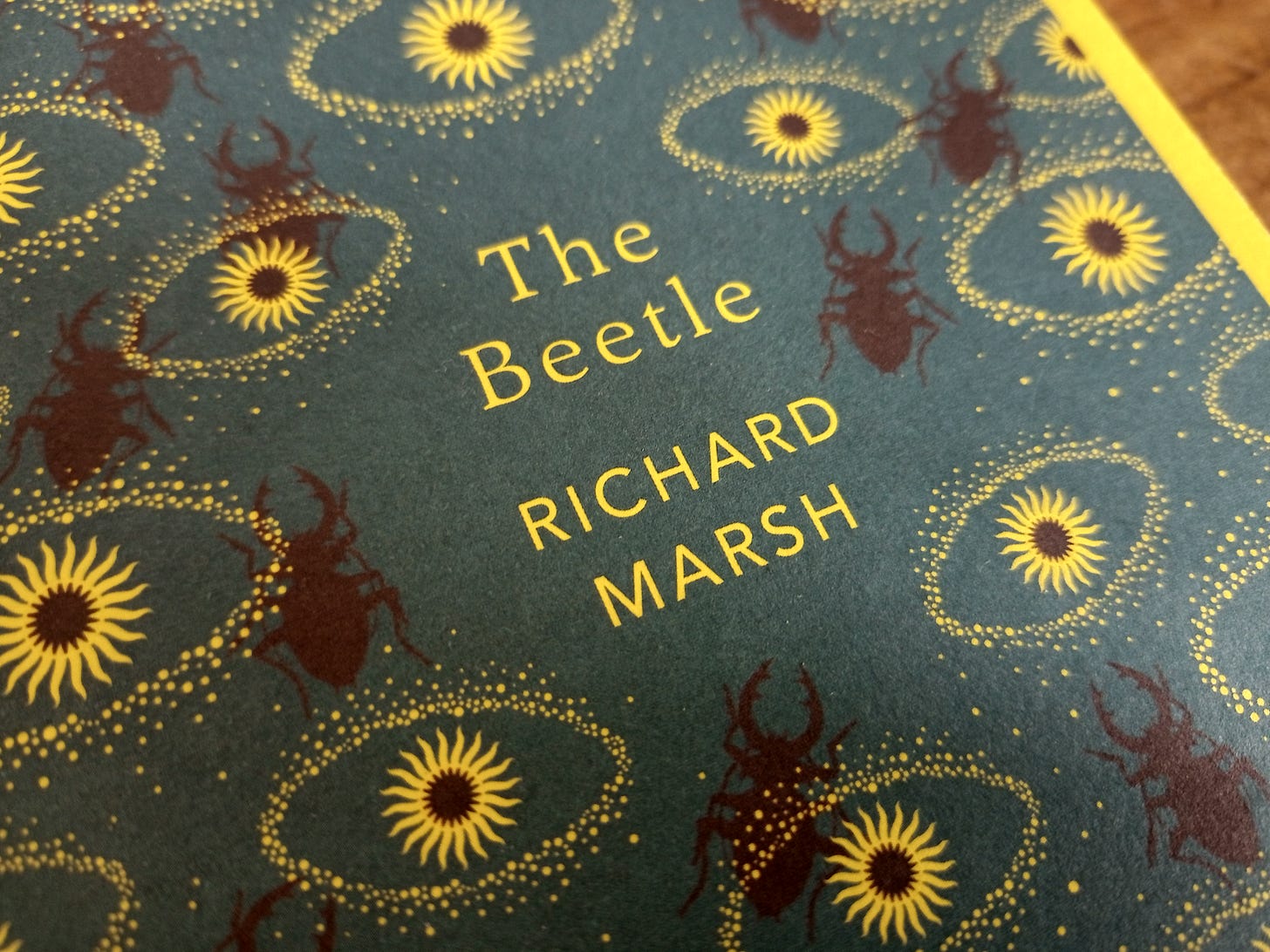

I’ve begun reading The Beetle by Richard Marsh, “a thrilling horror novel of mesmerism, murder and shape-shifting terror”, according to the blurb, released the same year as Dracula. Coincidentally, it includes a chapter very early on which could easily have served as the inspiration for some of Dishonored 2’s levels. Under the influence of mind control, the protagonist scales the outside of a house and smashes his way through an upper floor window. The house belongs to a powerful politician, and our burglar has been sent to steal some papers – the key to that politician’s downfall.

It’s very Hammer Horror so far – short chapters making it easy to read at the bus stop.