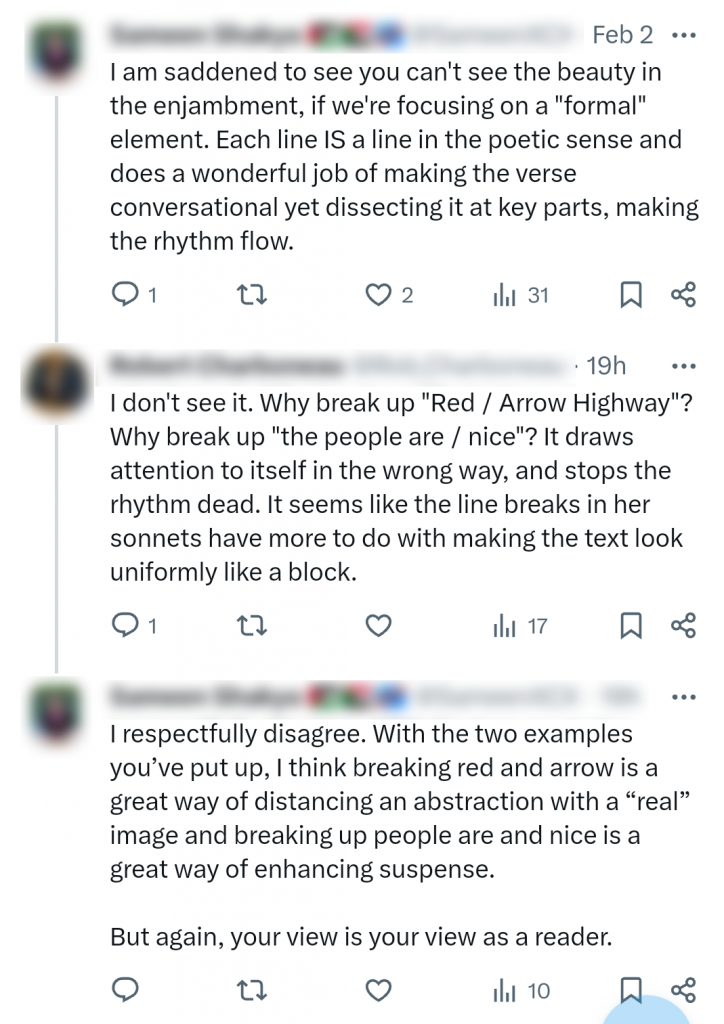

Here’s a rare sight indeed: a discussion of poetic form and its effects (or lack of them) on Twitter/X:

It’s a source of frustration to me that you’re only likely to see such exchanges in the wake of a spat or controversy, as in this case. I don’t agree that social media, as a forum, is especially ill-suited to hosting debates about poetry, or anything else for that matter. The problem is the icy stand-off between attitudes of thought that are equally rigid. On the one hand you have an ever-present, stiff-collared conservatism that pines for orderliness and reassuring authority in everything. From this attitude emanates the demand for a stable ‘definition’ of poetry and a carefully managed system for sorting it into gradations of quality. The worst adherents to this school profess an awe for the ‘beauty’ of classical formalism, but seem to be mainly motivated by their discomfort with both the volume of contemporary poetry and the volatility of the tastes and passions underlying it. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that they regard art primarily as a means for them to pose as refined beings, and resent anything that makes them feel they’re outside a scene. Those on the less extreme end of the scale, meanwhile, are often just bemused that the rules they were told to follow themselves are no longer in play, but lack the means or inclination to work toward a new evaluative framework.

On the other side, we have a supposedly more generous, more egalitarian position that denies, sometimes playfully (but mostly defensively), that there is any kind of consistency at all to what constitutes a poem. Its advocates frequently fall back on flimsy maxims like “I know it when I see it”, or “It’s a poem if it makes me feel something”. The problem here is a failure to recognise just how smugly elitist it can look when the in-crowd insists to frustrated outsiders that their club has no rules. Clearly, there is some sort of mechanism by which a poem leads one or more of us to ‘feel something’, to recognise something of value, and if we’re too lazy or too possessive to make any effort to explain what that is, then we invite speculation that the secret sauce is really favouritism of some kind. There also exists the not-unfair perception that those on the meagre gravy train of arts funding don’t like to talk about why a poem works or doesn’t work because it gets in the way of the endless sensationalist bluster that needs to be performed in order to keep paying the bills and feeding the ego.

Between these positions lies the vast potential to have conversations about the different values and expectations each of us brings to reading a poem, why the same small block of text might provoke feelings of joy in one person, feelings of fury in another, and nothing at all in a third. Occasionally one such conversation breaks out, but it’s all too often a brief interlude in a major bust-up, one that ends once the big factions have retreated to their respective corners and habits, muttering sourly at each other. What if we were to alter our expectations, such that distinct experiences of the same poem were something sought out as an opportunity for learning, rather than something mostly avoided – something which, once brought to light, can only be resolved by the conclusion that one or other person is a nitwit?