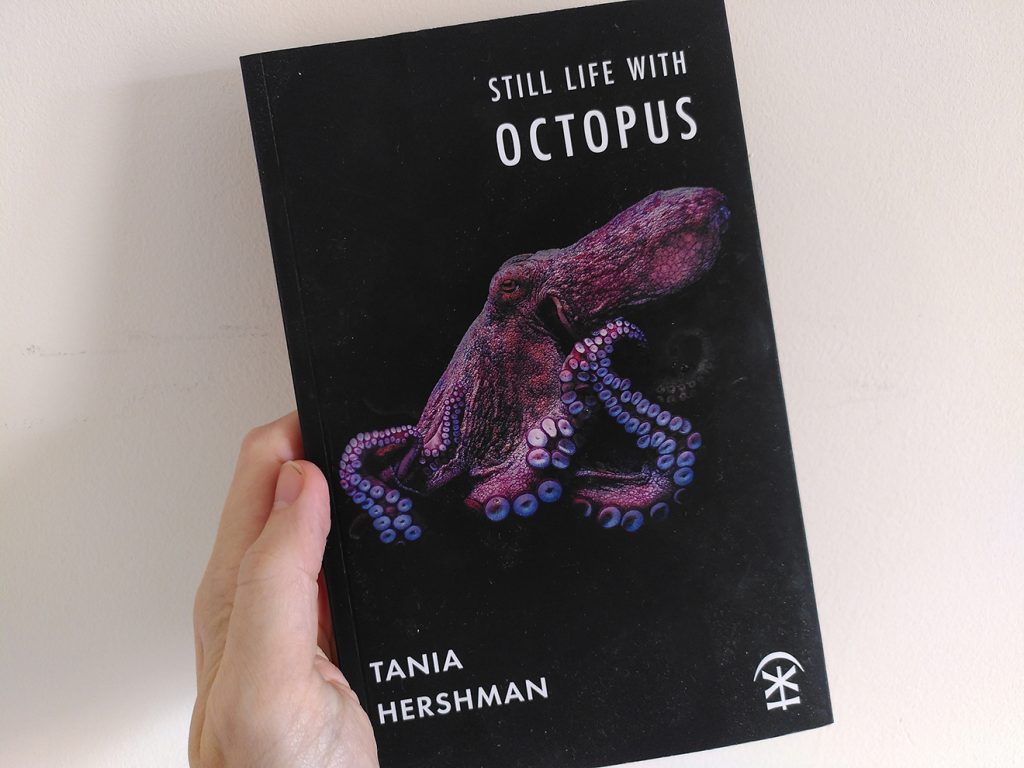

The poems in Still Life With Octopus slip down very easily — sometimes a little too easily, like they’re elastically escaping their tank. You think you’ve got them in focus, and then they’re gone. Not literally, of course; you can head back to the top of the page and comb them again, looking for the knot to unpick, but sometimes it keeps evading you. Take ‘What You May Be Offered’, for instance. It begins:

A man in a van stopped to ask

if I wanted a mattress. I said

no …

And it ends with the narrator in the same place, engaged in the same activity, one full day later, “wondering / what [else] someone might offer me”. The mystery here (and it’s not an unwelcome one) is what’s going on beyond the level of the starkly anecdotal. Who is this man? What does he have to do with the book’s broader themes, or its central sequence, in which an octopus is presented as a sort of younger conjoined twin living inside the narrator’s chest cavity?

Objects are fused with the body in other poems too — the book has a light, breezy tone but not infrequently deals in mild horror. In ‘What Plays Today’, it’s a radio trapped “between my ears”, which sometimes screams. In ‘And a Clock’, the mouth is stuffed with both the clock (which is broken) and a load of feathers. It’s a dream-poem, but the dream is clearly a nightmare — a tree comes alive in it and asks “Tell me who // this me is”. A few pages on, night itself comes to stir the narrator and ask for company, and a little way further on from that, a flickering light takes on the persona of ‘My Moon’, and likewise imposes itself as a fully self-willed entity in need of a place to stay. These briefly-sketched characters manage to come across as both creepy and innocent. In ‘I am interested’, the narrator even announces themselves as a stranger in their own body, intrigued by its mechanisms.

Still Life With Octopus begins and ends with poems titled ‘Arrival’, and is full of things arriving or becoming, or suggesting they might like to be more deeply involved with one another somehow — the theme of tying, sewing, stitching recurs as well (‘Psalm for the Seamstresses’, ‘Tied’, “I tie it with string” in ‘When the Time Comes’, “reel / her in” in ‘Tango’, ‘How to Make a Buttonhole Hand Stitch’), and the octopus as symbol of fleshy entanglement is never far away. Body parts — chiefly, internal organs — and their relationship to one another also come to the fore more than once, and the closing ‘Arrival’ poem reads as a set of Ikea instructions for (mis)handling human/animal intimacy:

put me down

until I lift me

put me aside

until I can lean

put me out

until I desiccate

I guess, then, that the man with the mattress for sale in ‘What You May Be Offered’ is trying, in a timid sort of way, to cross a boundary, to join in with the awkward intermeshing that is taking place elsewhere, to “start with pieces, end with objects” as the seamstresses do. There’s a weird, slightly menacing craving for ease and harmony throughout Still Life With Octopus that’s barely even hinted at in the cover blurb, but which is certainly present in the animal totem Hershman has chosen — and even, perhaps, in the title. ‘Still Life’ — a contradiction-in-terms, no?

(Read next: Lyonesse / Penelope Shuttle).