Lyonesse (Bloodaxe, 2021) presents a problem. On the one hand, it’s tricky to talk about because I don’t feel able to map out the book’s depths. Parts of it remain sunken and mysterious to me – I can claim no commanding vantage point, despite having browsed it on-off for a couple of months and read some of the poems upwards of a dozen times.

On the other hand, it’s tricky to talk about because it describes itself, its themes and its subject matter clearly enough without any need for me to add gloss. In the preface and on the cover and in the poems themselves we are introduced to Lyonesse as “a submerged land”, “a city under the sea”, “an emblem of human frailty in the face of climate change”, “a fluid magical world”, “a feasting-cup city”, “just what you want it to be / streets paved / with the sea”. And in a sense, this is all we need to know; the poems expand on and exemplify these core traits, even foreseeing my present dilemma by referring to Lyonesse as “a place of paradox”.

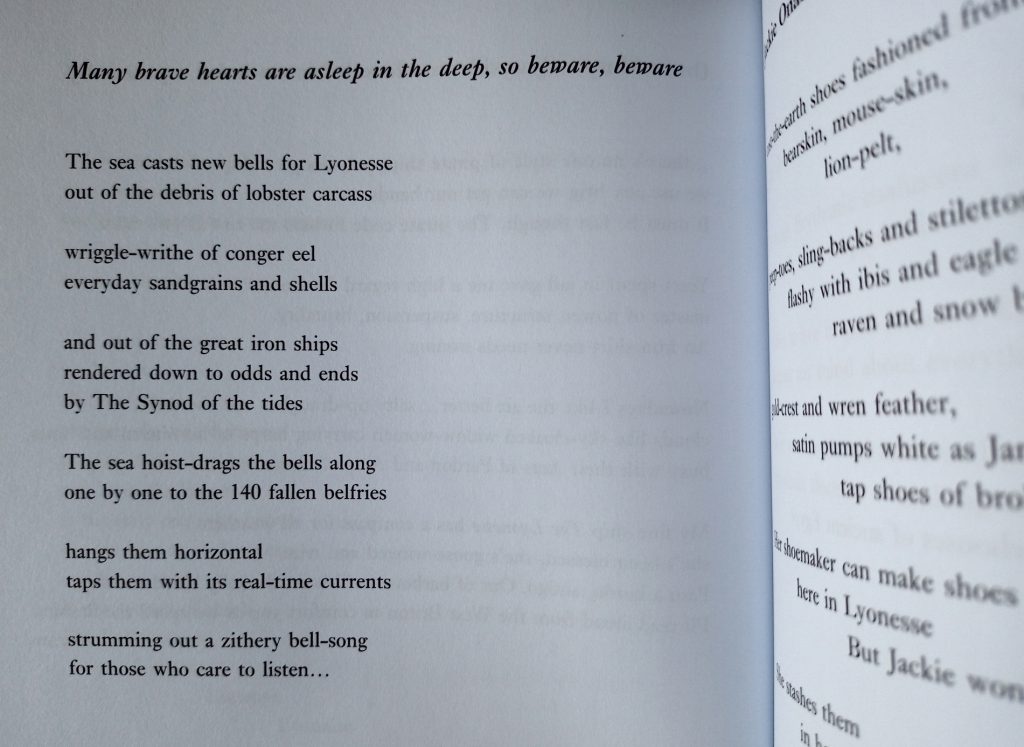

The poems are also characterised as a series of ‘soundings’ that test the weight and the character of the Lyonesse concept through propositions, and by answering their own questions. How are bells made in an underwater city? They are cast out of lobster carcasses. What would a church service there comprise? Well, the ‘Crayfish Christ’ would have this to say:

Beloveds

Church of Crayfish Christ

you must live for pleasure alone!

This is my gospel

Am I not half-brother to the moon?

Are not the deeds of my claw everlasting joy and delight?

Thus Lyonesse accumulates history and character. A close reading seems redundant; the book is a Lonely Planet guide. It fills you in on all the details, and repeats its own title so often that ‘Lyonesse’ becomes a spell in itself, a magic word, the repeated hissing and breaking of waves.

I found as well that the poems flow into one another – that it’s hard to recollect, when I don’t have the book in front of me, which images came from which poem. Their forms are varied, making use of different margin alignments, stanza shapes, spacing, titling conventions, and so on, in the manner of different wind-driven slices of the sea colliding and dispersing (or pieces of shipwreck washed up on the shore). The collection avoids feeling like it’s settling into a routine or iterating a pattern.

There are several poems where the lions of Lyonesse make an appearance (sometimes they are princes) – and there are owls of Lyonesse too, and gownshops and quaysides, and echoes of other myths drawn in and chewed in the surf: an interview with Neptune, plus mermaids and sirens, the devil, Davy Jones. Sometimes the narrator is a resident (a survivor, or a fortune-teller), other times someone hearing and passing on the story.

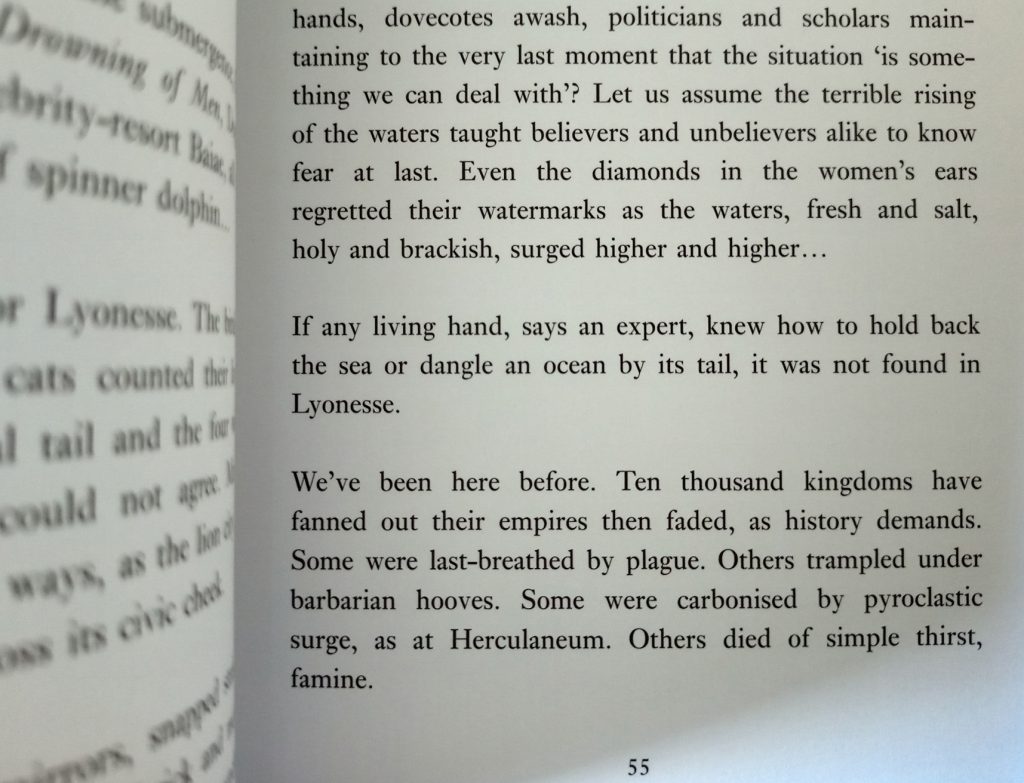

Many of the poems allude to Lyonesse’s fate, and it’s in this respect that the book is most beguiling, since there’s no actual timeline to be grasped; the city is now and was always both sinking and sunken, destroyed and renewed. It is sea-ravaged, sea-remade, of the sea and entwined with the sea, there and not there. There’s a central ‘Account of the Submergence’, which is composed in full paragraphs and more than two pages long. This poem feels like the anchor, the true tale at the heart of all those others swimming about it, but even here the story remains evasive, partial and teasing (‘Now that we have wiped Lyonesse from the Departures Board (the starry way to Lyonesse no longer valid) let us record what we know so far’).

I think of this line from Auden: “In so far as poetry, or any other of the arts, can be said to have an ulterior purpose, it is, by telling the truth, to disenchant and disintoxicate.” What truth is being told here, about human frailty or climate change? Perhaps that we have made these such a central part of our collective identity that we can no longer imagine what it would be like to not be in the midst of a vast, drawn-out episode of avoidable calamity. We don’t regard the end of civilisation as a series of events so much as a state of being that has been with us throughout our time as a dominant, sentient and self-directing species.

The preface is an interesting and unusual inclusion – I know others tend to find explanatory essays needless at best, an imposition at worst. In this case, I think the only issue is that it ought to be at the end of the book, not at the beginning, since it provides such a ready key to the poems that it risks turning them into a mere demonstration of a thesis. I preferred, for the most part, to put out of my mind the climate parable aspect, and become lost in Lyonesse as a tourist with an outdated, part-perished map becomes lost in a ghost town.

The preface also makes clear the role of grief in the poems, and I should mention here the second and final section of the book, ‘New Lamps for Old’, which moves away from Lyonesse (though not entirely) and into a house deeply haunted by the author’s memories. The poems here are more straightforwardly personal and direct, a little more terse and spare and grounded. The effect is like reaching the end of an animated film and then being shown a reel of the animator getting up from their desk. I like this – it avoids the usual disappointment I feel when a book’s major sequence is too short to stand on its own and seemingly needs to be bolstered by a lot of scattered miscellaneous pieces. ‘New Lamps for Old’ seems set both inside and outside Lyonesse, as if we could zoom out one stage further and find we had been lingering in a snowglobe in one of the city’s gift shops.

This is really a testament to how fiercely (but delicately) the book evokes a sense of place. To open it again after a time away is to return through a portal to somewhere that can never be comprehensively charted, a shattered Narnia that is at once very, very far away and right on the cusp of our own world.