How does a poem mimic (or capture, or transmute) something so visual, so kinetic, so unliterary, as the sight of a murmuration of starlings? And is there any point in it trying to, when we can see the spectacle for ourselves at any time, via a brief internet search? Where is the sense in using such a tired machine as language – words on a page – to describe something that can be experienced first hand?

Let’s look at how two different poems answer these questions. Holly Hopkins’ ‘Starlings’ was first published in Birdbook: Towns, Parks, Gardens and Woodland, a book I co-edited in 2010, and has been most recently printed in her Forward Prize-nominated collection The English Summer. Caleb Parkin’s ‘The Starling Committee Decides’ is published in Raceme no. 13.

‘Starlings’ is written in iambic tetrameter and composed of rhyming four-line stanzas. This is a form that’s easy to read quickly, almost breathlessly, because it’s broken into same-sized units, which are themselves broken into same-sized units. Each four-line stanza is made up of two rhyming couplets. Each couplet is made up of two lines. Each line is made up of four beats. Each beat is made up of one stressed syllable and one or more unstressed syllables. This is about as straightforward as language-patterning gets, and thereby allows the eye and the ear to move forward at pace.

The poem is also a cascade of images, one after another after another. There are no scene transitions and only the thinnest commentary is offered; instead, we move from fens as ‘dying seas’ to sedges, to marsh, to ragged lines of starlings, a ‘budding, chirping swell’, ‘kneaded dough’, a ‘churning shoal’, a ‘living sack’, a ‘thread of trust’ and so on. It seems on a first read-through that the murmuration only takes shape in the second stanza, and that the way the poem tries to capture the spectacle is through those images in the second, third and fourth stanzas, all of which are apt but, one might argue, not a patch on seeing the thing with your own eyes.

But it’s the combination of form with rapid succession of images that provides the more compelling imitation. ‘Starlings’ moves in the mind just like a miniature murmuration, one shape changing to another at speed: swell into flow, flow into dough, shoal into sack, sack into thread. This sets up a contrast with the watchers described in the poem’s last stanza, who stand ‘locked inside their coats’, not daring to speak because of their uncertainty about ‘blundering’, failing to synch up with one another. Human self-consciousness is here starkly presented as a frailty, an inability to harmonise, with the effect that progress is brought to a standstill.

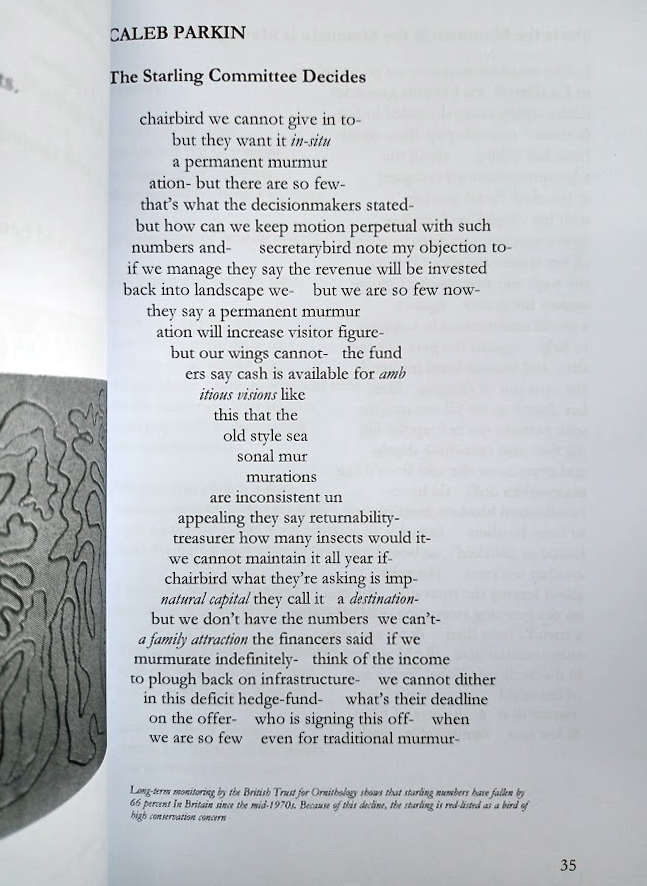

‘The Starling Committee Decides’ takes a different approach. The poem is shaped like a snapshot of a murmuration, with the individual words as individual birds. This makes its rhythm rather bumpy, since the lines are all sorts of different lengths and don’t even start at the same left-hand margin. Parkin adds to this effect by splitting words across lines (‘murmur/ation’, ‘fund/ers’) and using multiple voices which interrupt and talk across one another. It is, as the title indicates, a portrayal of a committee – the voices are not so distinct that clear characters emerge, so we are left with an impression of a squabbling, disorganised cacophony.

As in Hopkins’ poem, there is a strongly implied contrast. The starlings here are humanised, deploying bureaucratic jargon (‘returnability’, ‘natural capital’) and in clear disagreement as to how to proceed. They keep referring to murmuration but have lost the ability to murmurate (‘we don’t have the numbers’). Parkin has frozen them in two ways: by deploying the poem as a still image, and by imbuing them with human reason and individuality.

Both poems suffer from eco-anxiety; ‘Starlings’ begins with a reference to the deterioration of the fenlands, while ‘The Starling Committee Decides’ is premised on reports of collapsing starling populations, handily explained in a footnote. Both respond to this anxiety by turning the spectacle of murmuration back on its human observers. One uses the speed and sweep of language, turning its eye on us very suddenly; the other makes use of the writer’s ability to pause and rearrange, so that we recognise the detail of the accusation. Both seem to agree that we are too young and inexperienced, as individuals, to know how to pull together as a species.

LINKS:

Birdbook: Towns, Parks, Gardens and Woodland

Holly Hopkins’ The English Summer