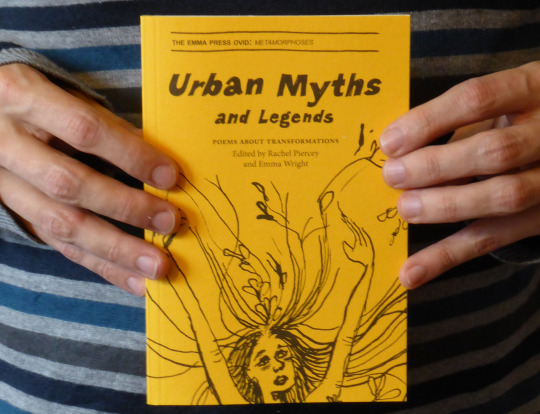

I have a poem, ‘Yardang’, published in Urban Myths & Legends: Poems About Transformations, edited by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright, and published by The Emma Press. It’s hard not to note how apposite the theme of this anthology is, particularly given the emphasis (which Wright notes in her introduction) on unwelcome, disturbing forms of transformation – forced shapeshifting as punishment, or as part of an experiment.

Fear of irreversible change seems to be the driving force behind all the major political narratives of the past twelve months. I was hoping to do a little pontificating about personal change here instead – how I find artistic consistency a strange and incredible feat since it seems like a different would-be genius takes over my body every other day of the week, and as a result I expend far too much energy trying to refine my strategy for maintaining something akin to a steady trajectory. How completely impressive but also threateningly inhuman I find any portrait-profile of a poet that recognises a ‘great project’ or single over-arching goal throughout their work (how do you avoid constantly changing your mind about something like that?). How, despite the aforementioned chaotic internal shapeshifting, I feel like the public me is a hopelessly sluggish changeling who is always tinkering with exactly the same ill-defined contraption as the last time you spoke with him. How deft and speedy the personal and artistic evolution of others seems to be in comparison – like that David Bowie gif which did the rounds, flickering from one face to the next. How I know this to be at least somewhat illusory, because I have myself been accused of being the same omnipresent, quick-switching climber as my own tormentors.

I’m not sure how much of this is symptomatic of the broader exasperation with too-slow, too-fast change. In the past, when I’ve tried to understand political conflict, in a very general way it has always looked like movement versus inertia. Usually small-c conservatism versus a radical liberal agenda. Now, with the EU referendum and the rise of Trump (it exasperates me even to have to type his name), there is a sense in which all sides are trying to stop the clock. Brexiters and Trump supporters want to halt free movement and stymie the advancement of multiculturalism, while Remain campaigners and the non-Trump-supporting portion of the US fear the mobilisation and growing influence of the far right. Nobody wants their country to be forcibly transformed; everyone suspects their enemies of wilfully visiting an unnatural transformation upon them.

Even the success of Corbyn in the Labour leadership elections has elicited genuine horror from a political faction (you can call them the centre-left or Blairites or anything you wish) who consider it a hostile takeover of their party, and who have subsequently behaved as petulantly as the worst elements of every other group that feels unjustly sidelined. It’s as if a series of heavy blows have been dealt to the philosophy that through slow and careful calibration you can keep all styles and varieties of discontentment in check. If that strategy no longer works, then at some point you have to work out who, or what, you are going to actively oppose and seek to repress. Naturally, at that point, the differences between us become starker and uglier. Tentative alliances fall apart.

I suppose my concern is that we’ve reached a point where all movement in any direction causes hurt and ructions. I feel like I now have a pretty good handle, for instance, on the frustrations of Brexit voters who want a cap on immigration, and I can sympathise with them. When the IMF says that immigrants are “overrepresented in higher-paid (as well as lower-paid) jobs” because they are better educated, and that immigrants therefore have a net positive effect on productivity and economic growth, the corollary of that is that they are indeed taking jobs from UK natives. But what is going to happen to working class communities if productivity and growth fall? And are Labour, or anyone else, supposed to now subscribe to a lie about the positive effects of (further) restricting immigration in order to regain the trust of working class voters, sanctioning resentment towards immigrants in the process? Obviously not. So where is that vote going to go except to UKIP, and possibly parties even further to the right?

I cannot envisage a top-down strategy that will work for any of the mainstream political power blocs right now. The referendum, as well as the US election, will be decided on feeling; that is, whether there are sufficient numbers whose desire for control is so desperate that they will take extreme action in order to satisfy it. It’s the same principle, so far as I understand it, as self-harm. But you cannot simply give these people more control without taking it away from others. There just isn’t enough control to go round.

A yardang, by the way, is a kind of slanted rock formation carved by desert winds. Hence the opening line of ‘Yardang’ is “The jackal wind is changing me”. With the exception of this and the near-identical ending line, the poem uses a shifting chain of synonym end-rhymes all the way through, so ‘degree’ moves to ‘extent’ to ‘scope’ to ‘reach’ and so on – gradual adjustment.